Risk Management

| << Back | Download |

Young ophthalmologists on trial

PAUL WEBER, JD, OMIC Vice President, Risk Management/Legal

PAUL WEBER, JD, OMIC Vice President, Risk Management/Legal

For a physician, it is not a matter of if but when you are going to incur a malpractice claim. Over the course of a 35-year career, 95% of ophthalmologists will have at least one claim against them and more than half can expect two or three.

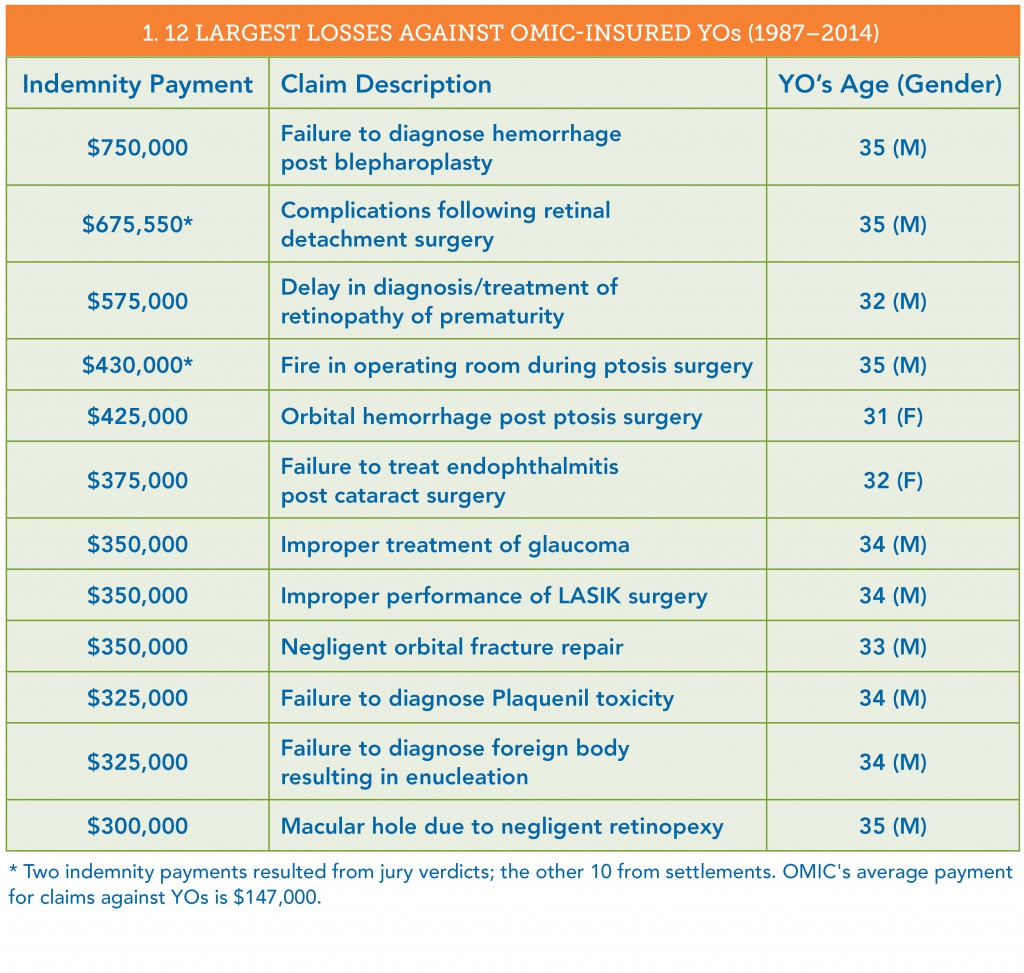

Since 1987, OMIC has closed more than 400 claims brought against young ophthalmologists (YOs) (see Table 1).

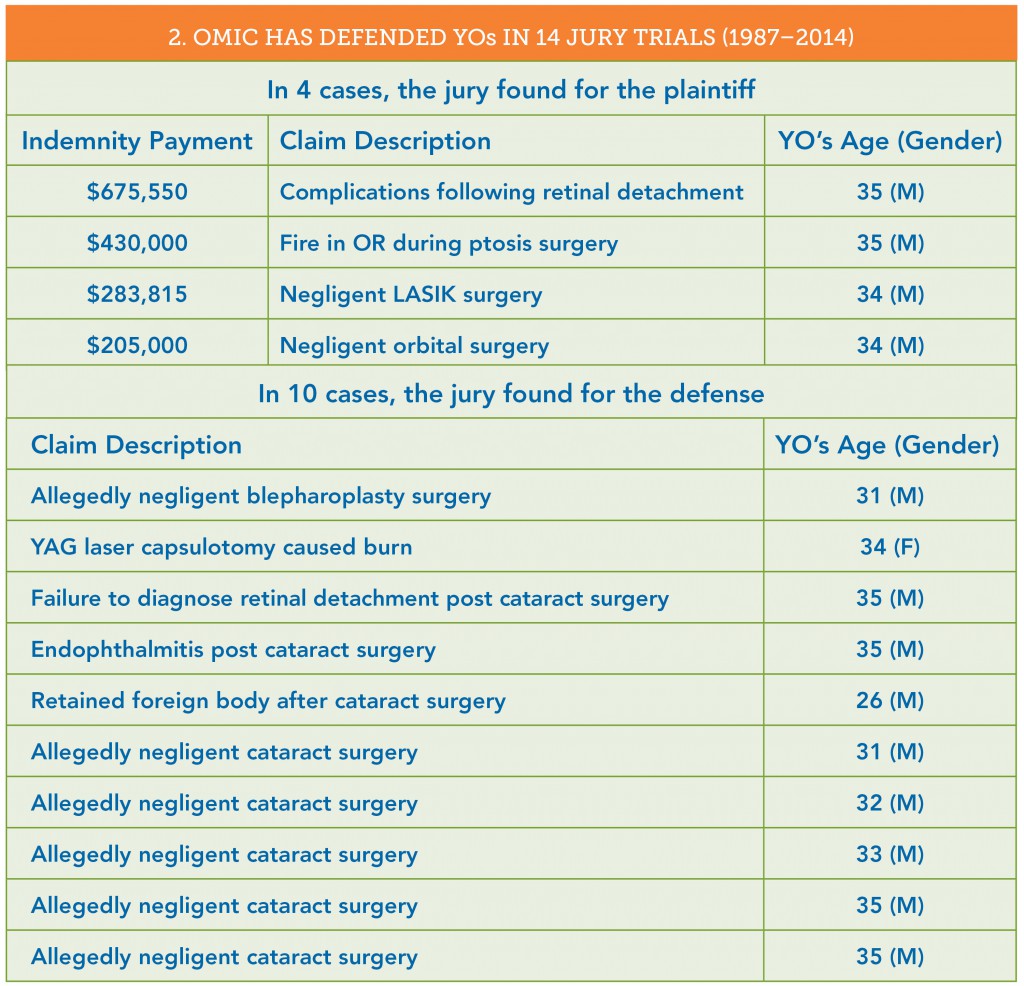

- 14 of these claims went to a jury trial; the jury found for the plaintiff in 4 cases and for the defense in 10 (see Table 2).

- 20% of these claims were settled out of court with an indemnity payment to the plaintiff.

- 80% of these claims—many of which were found to be without merit—were closed with no payment. In 15% of the cases, there were not even defense costs associated with the claim.

The cases that follow will help you understand some do’s and don’ts to minimize the risk of serious litigation.

A $750,000 payout

The largest loss in a claim against an OMIC-insured YO was $750,000 for failure to diagnose a hemorrhage that resulted in eventual blindness (no light perception) in the patient’s left eye following a bilateral blepharoplasty.

The plaintiff initially focused on the insured’s lack of experience because this was the first blepharoplasty he had performed since his residency. The plaintiff’s lawyer was prepared to suggest that the YO lacked the requisite skill and experience and thus contributed to causing the hemorrhage and poor postoperative care.

The real problem was the patient’s chart. First, the YO did not document visual acuity on the first postop visit on August 21, five days after surgery. (The patient later testified that she was “blind” in her left eye at that visit.) The patient never returned to the YO. She went to another ophthalmologist a week later on August 28 and was found to have light perception only in the left eye.

What made this case indefensible occurred on September 5. After learning that the patient was blind, the insured began “supplementing” the patient’s medical record. First, he changed and added information to his original preop note concerning informed consent. The original note read “Discussed risks, benefits, and alternatives of bilateral blepharoplasty. She agrees and wants it done.” The new note, written several weeks later, read “Discussed risks, benefits, and alternatives of bilat bleph in detail. She agrees and wants it done. We discussed no ASA, blood thinners, garlic, Vit. E, red wine for two weeks before procedure. She understood.”

There also was a late dictated chart entry for the August 21 postop visit. On that day, after the postop visit had taken place, the physician apparently called his technician and asked her to make an entry in the patient’s chart. He later added his own note on September 5. Unfortunately, the two notes were inconsistent in that the insured’s own note stated he performed an optic nerve and retina exam, but the earlier dictated note did not. The plaintiff claimed that all the changes to the medical record were self-serving and the insured was trying to “cover himself.”

Trouble at the deposition

Before trials take place, attorneys can question litigants and other important witnesses during a deposition. This allows both sides to gather evidence for the trial. The witnesses are under oath, and a court reporter transcribes the testimony, which is sometimes videotaped. In this case, when the YO was being examined at his deposition, he became very flustered and had great difficulty answering questions. When asked whether it was important to keep medical records for the health and safety of the patient, he answered “No.” When asked whether it was important to keep accurate and complete medical records, he first answered “No,” and then “It depends on the circumstances.” He stated that he had supplemented the record to make it more “clear” to him. It is quite possible that he made the changes to more accurately reflect what he did and said at those office visits, but the plaintiff’s attorney would paint the changes in the worst possible light. With the consent of the insured, OMIC settled the case prior to trial.

Changing documentation is problematic. When you have had a bad outcome or serious complication, beware of supplementing or adding to your prior notes. Sometimes changes must be made after these events because you don’t want inaccurate or incomplete information being sent and relied upon by subsequent providers. When these situations arise, you should get advice—call OMIC, your malpractice insurance company, or your personal attorney.

Voices of experience

OMIC insureds who have been through litigation offer this advice:

- Maintain absolute integrity of the medical records.

- Document all phone calls.

- Have a session with staff about the importance of charting no shows.

- Start charts with ER call. Contact patients if they fail to show.

- Rely less on staff to ensure documents are properly executed.

- Document that no guarantee was made regarding outcome.

- Have longer preop discussions.

- Be open with patients about complications.

- Use procedure-specific consent forms.

Informed consent is critical

Every surgical procedure requires informed consent. Although all of the following four cases involving cataract surgery resulted in a verdict for the defense, they demonstrate that informed consent is more than just having a patient sign a form.

Case 1: Plaintiff expert was critical of the fact that the physician performed the procedure without informing the patient of the minimal benefits anticipated from the surgery. The patient had a history of glaucoma, a small and poorly dilated pupil, and a branch retinal vein occlusion.

Case 2: Plaintiff expert stated that it was below the standard of care to not advise the patient that he had lattice degeneration and that this increased the risk of retinal detachment. There was no note in the chart regarding an informed consent discussion.

Case 3: Plaintiff expert stated that the physician should have informed the patient that he was a relatively new ophthalmologist and had not performed cataract surgeries outside of his residency program.

Case 4: Plaintiff expert testified that the physician did not properly provide informed consent because he did not provide alternatives, and that there should have been a consent form in the chart signed by the patient.

Key steps for informed consent

It is certainly important to have a patient sign a procedure-specific informed consent document, but there are other steps you should consider.

Document your discussion with the patient. This should include:

- Time. Note the specific amount of time you spent with the patient (or his or her guardian/caregiver) explaining the risks, benefits, and alternatives.

- Who was present. Note who was in the room when you had this discussion (e.g., patient’s spouse, adult child, your staff).

- Who translated. If the patient’s English is limited, document who was translating.

- Comprehension. Note how you determined that the patient actually understood what you discussed (e.g., the questions used to determine comprehension).

Document what information you provided. Document that you gave a copy of the signed consent form to the patient. You also should document when you provide patient education materials (e.g., fact sheets) or when the patient views videos.

Document your informed consent process/protocol. Have a meeting with your staff to review and document the steps that are taken for informed consent. Save this written process/protocol, use it to orient new staff, and revise it as needed.

Create a checklist. Some physicians write down the issues that they always discuss with patients prior to a procedure and use this as a checklist. The checklist gets entered in the patient’s chart. Take advantage of OMIC’s guidance on informed consent available at www. omic.com/informed-consent obtaining-and-verifying/.

Emotional impact of a claim

Regardless of whether they win or lose a lawsuit, physicians who are sued are at risk of severe emotional distress. Resources to deal with the anger and other difficult emotions that might arise during and after litigation may be found on OMIC’s website at www.omic.com.

A malpractice lawsuit can be emotionally traumatic, but physicians eventually see their cases through and often emerge stronger and even more committed to their chosen profession:

“I was able to get through this horrific ordeal relatively unscathed, but a bit stronger from my scars. The

phone call I received informing me that my case had been dismissed ranks, in terms of emotional impact, just below that of my children being born.”

“I am humbled at the experience I have gone through during the four-year process. I am grateful to be insured by OMIC and to have the representation that I had to help resolve the case prior to trial. I hope to be able to share my experience with others so that they understand that, while frustrating, the process works.”

“It was a very stressful experience, but I am a wiser doctor for having gone through it.”

This article was first published in EyeNet Extra: A Guide to Practice Success (August 2015), a supplement written specifically for young ophthalmologists.