Call early, call often: Benefits of proactive incident reporting

PAUL WEBER, JD, VP, OMIC Risk Management/Legal, and MICHELLE PINEDA, MBA, OMIC Risk Management Specialist

OMIC handles hundreds of claims and lawsuits every year. However, many insureds are unaware of the additional benefits and services beyond claims handling that OMIC provides to policyholders and their staff. Over the past five years, OMIC has spent more than $1.8 million to help insureds proactively manage a myriad of sensitive, complex liability issues that were not malpractice claims. This Digest reviews some of these events and the value of calling OMIC early and often when they occur.

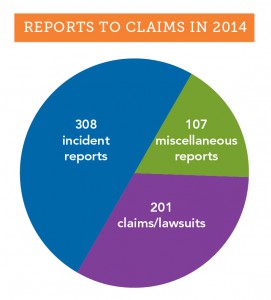

Reports to claims department

In 2014, OMIC’s claims department received over 600 reports from insureds. Of these, 201 were claims

(written demands for money) and lawsuits, and the rest were incident and miscellaneous reports (see graph). Most of the 415 incident and miscellaneous reports were what OMIC considers “potential claims,” events that may result in an actual claim or lawsuit. Such events include oral demands for money or services, medical records requests, adverse outcomes resulting from patient treatment, and other signs the patient may be dissatisfied with treatment. An early call to OMIC’s claims staff starts the process of coverage for a potential claim. Staff will provide guidance on steps to take to minimize the impact of the incident. Some incident and miscellaneous reports don’t fall clearly into the potential claim category. As illustrated in the case study that follows, these matters may arise in an unusual manner and require significant claims and legal assistance before they are resolved.

OMIC insureds are encouraged to contact the claims department whenever they are requested to give their deposition in a malpractice claim so OMIC can determine whether counsel should be assigned. Generally, they are simply being deposed as a “fact witness,” someone who was a treating physician or consultant in the plaintiff’s care. In these cases, OMIC may assign counsel to make sure the insured’s testimony is limited to “facts” and does not include conjecture.

In May 2013, an insured contacted the OMIC claims department thinking he was going to be deposed simply as a fact witness (consulting doctor) in a lawsuit against another physician and a hospital. The plaintiff had undergone gastric bypass surgery. In the weeks following the surgery, the plaintiff was seen at the emergency department several times for nausea and vomiting. During one of these visits, the patient complained of blurry vision, confusion, low energy, and cognitive problems and was admitted to the hospital for further examination. The patient’s gastric bypass surgeon and an internal medicine physician were supervising her care, and the OMIC insured was called to consult on the vision problems. The ophthalmologist felt the patient’s blurry vision could be caused by a thiamine (B1) deficiency. As another physician had already ordered B1 and B6 testing, the ophthalmologist felt his consult report properly communicated his concern to the team of doctors caring for this patient. Unfortunately, none of the treating physicians reviewed the B1 test results, and about five days after the ophthalmology consult, the patient went into a catatonic state and was transferred to a psychiatric hospital. It was only then that the B vitamin test results were interpreted and the patient was noted to be suffering from an extremely low vitamin B1 level. She was diagnosed with Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome and given thiamine to treat the condition. The lawsuit against the surgeon and internist alleged delayed/missed diagnosis and failure to treat, which caused neurological injuries and permanent irreversible brain damage.

OMIC’s claims staff reviewed the notice of deposition and contacted local defense counsel, who determined that the plaintiff attorney might name the insured in the lawsuit. State law allowed the plaintiff six months after the notice of deposition to add defendants. The OMIC defense attorney carefully prepared the insured for his deposition, with the assumption that the insured might be named as a defendant. Accordingly, the attorney attended the depositions of other parties and witnesses to prepare to defend the insured if needed. During the deposition, the plaintiff attorney asked probing questions of the insured’s care, suggesting there should have been better follow-up. The plaintiff attorney also tried to get the insured to criticize the care of the defendants. Fortunately, the insured was well prepared, confidently explaining his own care without giving damaging testimony against the other providers. The OMIC insured was never named as a defendant. His call for deposition assistance limited his role in the lawsuit, ultimately protecting him and keeping OMIC’s costs to $10,000.

Reports to risk management

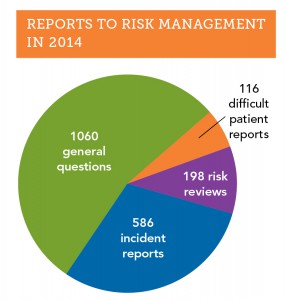

The risk management hotline is one of the most utilized and valued services that OMIC provides to its insureds.  In 2014, 1,960 insureds and their staff called the hotline (see graph). Over half of the calls had to do with general risk management issues, such as documentation and record keeping, informed consent, HIPAA privacy, and proper advertising. Calls about “difficult patients” were less frequent (116 reports) but were often challenging and time consuming because many aspects of care needed to be discussed, including the patient’s clinical and mental status, comorbidities, and payment issues. OMIC risk management staff work with the insured to craft an approach that resolves difficult patient situations so they do not escalate into claims.

In 2014, 1,960 insureds and their staff called the hotline (see graph). Over half of the calls had to do with general risk management issues, such as documentation and record keeping, informed consent, HIPAA privacy, and proper advertising. Calls about “difficult patients” were less frequent (116 reports) but were often challenging and time consuming because many aspects of care needed to be discussed, including the patient’s clinical and mental status, comorbidities, and payment issues. OMIC risk management staff work with the insured to craft an approach that resolves difficult patient situations so they do not escalate into claims.

Like the claims department, the OMIC risk management department also receives incident reports about adverse outcomes that may eventually become claims. In 2014, the risk management department received over 580 incident reports, approximately one-third of all calls to the hotline. Reports of incidents to the OMIC claims and risk management departments differ in important respects. First, all matters reported to the OMIC risk management department are kept strictly confidential; they are not shared with the underwriting or claims departments without the insured’s explicit permission. As a result, coverage is not triggered when an incident is first discussed with the risk management department, but insureds are encouraged to contact the claims department if the incident seems likely to result in a claim. At times, the best approach to managing an incident is to have risk management and claims work collaboratively with the insured, as the following case study demonstrates.

Last year, an insured called the risk management department to report a cluster of endophthalmitis cases in his retina practice. He believed the cluster arose from contaminated Avastin he had purchased from a compounding pharmacy in his state. On a Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, the insured had injected 46 patients with the same lot of 70 syringes repackaged by the compounding pharmacy three weeks earlier. By Thursday of that week, four patients injected on Monday returned to his office with endophthalmitis. All four were immediately taken to surgery, tapped, and injected with antibiotics.

The insured contacted the compounding pharmacy that same day and reported his strong suspicion that the Avastin was contaminated. He also spoke to OMIC’s risk management department and was advised to sequester the remaining vials of Avastin and to contact the state health department, the Centers for Disease Control, and the Food and Drug Administration.

Not knowing how many other patients might have been affected or the exact cause of the endophthalmitis, the insured contacted all patients treated for age-related macular degeneration that week, including those who received Lucentis or Eyelea instead of Avastin. The insured had to cancel all his regularly scheduled patients over the next few days and worked over the weekend and into the middle of the following week in order to examine all the patients he had injected. As a precautionary measure, he prophylactically administered Vancomycin to all patients who had had intravitreal Avastin injections. Fortunately, no other patients developed endophthalmitis.

With the permission of the insured, OMIC’s claims department got involved and assigned a defense attorney. The defense attorney learned that an ophthalmologist from another state had reported a case of endophthalmitis from Avastin, bringing the total number of cases to five. The Avastin had come from the same compounding pharmacy and had been repackaged on the same day as the lot of syringes used by the OMIC insured. The pathology results from all five cases showed the same variant of streptococci.

To ensure that other ophthalmologists were notified, the insured and OMIC staff contacted the American Academy of Ophthalmology and the American Society of Retina Surgeons. The FDA, which had already been informed, issued a MedWatch Alert announcing a “voluntary recall” by the compounding pharmacy. In the recall, the FDA stated that syringes had been distributed to ophthalmic practices in Georgia, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Indiana. MedWatch advised ophthalmologists to immediately stop using lots of the recalled Avastin and to report any reactions or quality problems.

The story was picked up by the media. ABC online news compared these cases to the fungal infections following injection of contaminated medications from New England Compounding Center and similar prior endophthalmitis clusters that led to blindness after injection of compounded Avastin. ABC quoted the owner of the compounding pharmacy as stating: “We don’t know if the problem is with the vial from Genentech, our in-house procedures, or the physician’s office.”

The OMIC insured was contacted by a New York Times reporter for an interview. OMIC staff and defense counsel advised him not to talk with the media as this might compromise patient privacy and hamper the investigations being conducted by the FDA and state health department. The health department inspected the insured’s office the week following the outbreak and reviewed medical records for all patients who had received intravitreal injections during the at-risk period. The review was aimed at identifying risk factors for infection and evaluating office infection prevention practices. Inspectors found no deficiencies in injection technique or medication storage and handling at the insured’s office; however, they did identify multiple deficiencies at the compounding pharmacy in its repackaging process and determined that it had not complied with United States Pharmacopeial Chapter 797 (USP 797) standards for compounding or with recommended best practices for compounding Avastin.

With the assistance of retina specialists at a local university, the insured continued to care for the patients affected by endophthalmitis. The patients made no mention to the insured of filing a claim or lawsuit. Nonetheless, within a few weeks of the incident, the insured received a request for medical records from a well known plaintiff attorney representing three of the four patients who had developed endophthalmitis. Several months later, the plaintiff attorney called the insured’s office and requested an interview. The insured immediately contacted OMIC and the defense attorney who had already been assisting him. The defense attorney advised the plaintiff attorney that he was representing the insured and that all further contact with the insured should be through his office. The plaintiff attorney assured the defense attorney that the only target of the claim was the compounding pharmacy. Despite these assurances, defense counsel was concerned that any information revealed during such an interview could later be used against the insured in a lawsuit. As a general rule, OMIC and defense attorneys advise against informal interviews with plaintiff attorneys. In this case, OMIC claims staff and the attorney decided to allow the interview as long as the defense attorney was present to monitor the line of questioning and terminate the interview if it appeared necessary. Moreover, counsel felt the insured had handled the cluster of endophthalmitis cases in an exemplary manner, exercising good judgment in his quick identification and treatment of patients and notification of regulatory agencies. The interview with the plaintiff attorney was uneventful.

By promptly calling OMIC after identifying the cluster of endophthalmitis cases, the insured was able to avail himself of assistance from both the risk management and claims departments. With their help, he handled the clinical crisis and notified governmental agencies and the ophthalmic community quickly and effectively. The attorney assigned by OMIC helped the insured deal with the compounding pharmacy’s representatives and the patients’ attorney. While most incidents reported to OMIC are not as complex as this matter, this situation highlights the ability of OMIC staff to quickly muster the resources to help manage a fast-breaking incident.

When is a physician–patient relationship established?

PAUL WEBER, JD, ARM, Vice President, OMIC Risk Management/Legal

Plaintiffs who sue for medical malpractice must show that there was a physician-patient relationship that created a legal duty. OMIC has addressed the issue of a duty being established when the physician has not personally seen the patient in the context of on-call coverage for the emergency department, coverage arrangements with colleagues, and new referrals from other physicians. Articles and recommendations related to these situations can be found at www.omic.com. This article reviews an ophthalmologist’s duty to a patient that may arise from appointments with prospective patients and curbside consults.

Q When is a legal duty established between physician and patient?

A Unfortunately, there are no statutes specifically outlining and providing guidance to physicians on the circumstances that create this duty towards the patient. Instead, the legal basis for the physician-patient relationship arises out of court decisions that create precedents and vary by state. While there is no majority consensus, in general, the duty is established when a physician affirmatively acts in a patient’s care by diagnosing or treating the patient, or agreeing to do so. This area of law has evolved over decades so that now a physician-patient relationship may be established even when the physician does not personally see the patient, refuses to see the patient, or is unavailable to see the patient. Once the relationship is entered into, the physician owes a duty to the patient either to continue care or to properly terminate the relationship.

Q Can an appointment establish the physician-patient relationship?

A The general rule is that an appointment by a prospective patient to see an ophthalmologist by itself is not sufficient to establish a physician-patient relationship since an appointment does not necessarily mean the ophthalmologist has affirmatively acted or agreed to diagnose or treat the patient. However, since there is no “majority rule” on these issues, if a prospective patient misses a scheduled appointment, OMIC advises documenting your efforts to contact the prospective patient. Ophthalmologists generally may decline a request for an appointment but should have a policy to inform the prospective patient of the decision not to examine, diagnose, or treat and provide information about other options for care, e.g., the local hospital emergency room, local medical society, etc. When an ophthalmologist has granted an appointment for a specific consultation or procedure within his or her area of expertise, a duty to the patient can arise even prior to actually seeing the patient. However, if upon meeting and examining the patient, it is determined that the anticipated care is not needed or is beyond the ophthalmologist’s area of expertise, the patient should be referred to someone who can provide treatment. Once treatment has begun, regardless of whether it is within the ophthalmologist’s area of expertise, a relationship has been created and withdrawing from care at an unreasonable time or without affording the patient the opportunity to find a qualified provider may make the ophthalmologist liable for a claim of patient abandonment. OMIC insureds are encouraged to call the risk management hotline when they have concerns about withdrawing from care.

Q Can an informal “curbside consult” establish a physician-patient relationship?

A In the recent past, an informal opinion about a patient provided as a professional courtesy to a colleague did not typically establish a physician-patient relationship. Generally, if the patient’s identity was not disclosed, the patient was unaware of the consultation, and the consulting ophthalmologist did not bill for the advice, most courts would not have found a physician-patient relationship. Now, however, courts are increasingly allowing medical malpractice suits to proceed against specialists consulted informally. For that reason, it is important to follow general rules to avoid unintentionally establishing a physician-patient relationship when providing a curbside consult:1

- When consulted by other physicians, (a) frame responses in very general terms; (b) suggest several possible answers, noting that all are dependent on the specific circumstances of a particular case; and (c) include disclaimer statements to emphasize that there is no formal consulting relationship.

- Beware of evaluating test results of any kind and rendering a specific diagnosis.

- Keep all such conversations/communications short. If contacted by a treating physician a second time, consider suggesting a formal consultation.

- Document any such consultations with the date of the inquiry, the inquiring physician’s name, the nature of the inquiry, and any advice given. Without a record of the advice given, the consultant will be defenseless should a claim arise regarding the consultation.

These rules are based on the article “A Doctor’s Legal Duty—Erosion of the Curbside Consult” by Kimberly D. Baker of the Federation of Defense Lawyers and Defense Counsel.

Regulatory and cyber (e-MD) liability resources

Coverage for the 14 different regulatory and cyber electronic media (e-MD) exposures is included in OMIC’s standard professional liability policy at no additional premium, subject to a per policy period sublimit of $100,000 per claim and in the aggregate. The sublimit for disciplinary proceedings related to direct patient treatment is $25,000. For a list and description of all 14 additional benefits included in your OMIC policy, visit www.omic.com/policyholder/benefits/.

On the policyholder benefits page you will find information under the following categories:

- Billing Errors (“Fraud and Abuse”) Allegations

- HIPAA/HITECH Privacy Violations

- Other Regulatory Exposures (DEA, Stark Act, EMTALA investigations)

- Licensure Actions

- Disciplinary Proceedings

- Cyber Liability and Network Vulnerabilities (e-MD)

With the move to electronic medical records, HIPAA and HITECH exposures related to cyber and electronic media breaches have increased for ophthalmic practices. Practices are also subject to a wide variety of potential losses as a result of network vulnerabilities, including damage to, or loss of, data. To assist policyholders, OMIC now has a dedicated web page devoted to cyber liability exposures. Visit the risk management section of OMIC’s website for articles, tools, links, and loss prevention resources.

Exclusively for policyholders

OMIC launched a Cyber Liability Risk Management Portal in 2014. Go to www.omic.com/risk-management/ for links to state-specific regulations, sample templates and protocols, employee notices and guidebooks, compliance plans, and coverage information. You must register or log in to MyOMIC services online to access the portal. The process is easy and takes just a few minutes. For live assistance, please contact the policyholder risk management hotline at 800.562.6642 (press 4) or email a risk manager at riskmanagement@omic.com.

What You Should Know about Rates and Dividends

The Board of Directors is pleased to announce a 25% dividend for all physician insureds in the form of a 2015 renewal premium credit and continuation of 2014 rates through your 2015 policy year. Issuance of the dividend requires that an active 2014 professional liability policy be renewed and maintained throughout the 2015 policy period. Mid-term cancellation would result in a pro-rata dividend.

Dividends appear on your policy invoice as a credit to either your annual or quarterly billing installment. OMIC issues dividends as a credit toward renewal premiums for two reasons. First, premium credits offer favorable tax implications for policyholders. Second, premium credits allow for easy and efficient distribution of dividends.

Each year OMIC’s Board receives a report from actuaries describing current claims trends and how they relate to rate levels for each state and territory. Using this information, we determine whether a rate increase or decrease for the current or upcoming year is warranted. Dividends, on the other hand, are generally determined on the basis of whether claims trends for past years are better (or worse) than expected. Because malpractice claims have a “long tail,” in which resolution often occurs several years after the incident is reported, trends are only evident after careful monitoring of claims over a significant period of time.

OMIC continues to reduce malpractice insurance costs through lower rates and paid dividends. In addition to average premium reductions of nearly 30% nationally since 2005, OMIC has announced dividend credits totaling more than $58 million since our company’s inception, outperforming our peer companies by a significant margin. Issuance of dividend credits is not guaranteed and is determined each year after careful analysis of our operating performance. OMIC’s philosophy is to return any premium above which is necessary to prudently operate the company and to do so at the earliest opportunity.

Misunderstanding Common in Consent Discussions

Anne M. Menke, RN, PhD, OMIC Risk Manager

Anne M. Menke, RN, PhD, OMIC Risk Manager

Informed consent laws in most states require physicians to advise patients of their condition, the proposed treatment, and the risks, benefits, and alternatives of the procedure, including no treatment. The standard of what to disclose is usually what a “reasonable layperson” would want to know before agreeing to undergo surgery. The plaintiff in a lawsuit for lack of informed consent needs to prove that he would have refused to consent if the surgeon had advised him of a risk he considered “material” to his decision-making process. As the following claim shows, ophthalmologists and patients may have very different understandings of what information is needed.

It was not surprising that a patient who suffered intraoperative complications filed a lawsuit after undergoing four additional surgeries. The claims made in the lawsuit were fairly common ones for ophthalmic surgery. The plaintiff alleged that the cataract procedure was not necessary, that his physician did not obtain his informed consent, and that the intra- and postoperative complications were poorly managed. The initial defense evaluation supported the physician’s care. The prior medical records refuted the allegation of unnecessary surgery, as they chronicled slowly worsening vision that was no longer corrected by glasses or contact lenses, culminating in a referral to the defendant ophthalmologist for cataract surgery. Challenging the claim of lack of informed consent seemed similarly straightforward: the eye surgeon had documented a discussion of risks and benefits, and the plaintiff had signed a detailed, procedure-specific consent form in the physician’s office as well as a surgery center form that briefly listed risks that included blindness. Finally, expert witnesses supported the ophthalmologist’s management of the initial complication—intraoperative floppy iris syndrome, which at the time of the surgery did not even have a name yet—as well as its sequelae (rupture of the posterior capsule, iris defect, glare, and retinal detachment).

As the investigation of the suit proceeded, the lack of informed consent allegation became central, and information emerged that helps illustrate the problem some patients encounter during consent discussions. The plaintiff acknowledged in his deposition and in court that he had, indeed, read and signed the cataract consent form. Nonetheless, he insisted that the crucial piece of information that formed the basis of his decision to agree to surgery was not in the form itself. It was instead the ophthalmologist’s response to questions about the rate of complications that “there’s hardly anything we can’t fix.” The plaintiff maintained, again and again, that without such reassurance, he would not have consented to the surgery and without the surgery, he would not have suffered harm. The ophthalmologist adamantly denied making any such statement. He remembered instead that the plaintiff wanted to have a sense of the frequency of complications and that he gave him an estimate of the more common ones. The plaintiff refused to dismiss the suit and the surgeon refused to settle, so the case proceeded to a jury trial. The trial monitor felt that the key moment came when the defense attorney elicited an admission from the plaintiff that just three months before his surgery, he had served as the attorney in a lawsuit against another ophthalmologist for lack of informed consent for cataract surgery, a role that required him to have extensive knowledge of the risks of that procedure. The jury returned a defense verdict after only an hour of deliberation.

Why don’t patients understand risk information?

It is tempting to dismiss this malpractice claim as yet another example of a frivolous lawsuit. While the defense verdict was appropriate, there are important lessons to be learned from this claim. First, the plaintiff no doubt suffered while dealing with the complications and five surgeries, despite his final uncorrected visual outcome of 20/30. Many patients who experience complications conclude that the surgeon must have done something wrong, and ophthalmologists would be well-advised to proactively address this issue with such patients. An even more compelling interpretation comes from the field of “health literacy.” While the plaintiff was an intelligent and experienced litigator, when seated across from the surgeon during the consent discussion, he was simply a patient whose fears may have impaired his ability to listen, reason, and make decisions. According to the National Patient Safety Foundation (NPSF), “health literacy—the ability to read, understand, and act on health information—is an emerging public health issue that affects all ages, races, and income levels.”1 The NPSF asserts that the health of some 90 million people in the United States may be at risk because of such difficulties. Studies of this issue show that most patients, even those like this plaintiff with a high literacy level, struggle to understand healthcare information and that those with limited reading skills or difficulty understanding mathematical concepts are particularly challenged. Low health literacy appears to be at the root of noncompliance and many medication errors and leads to higher healthcare costs and poorer outcomes. A review of the last five years of closed malpractice claims suggests it may also be a driving force in lawsuits alleging lack of informed consent. This issue of the Digest will present the results of this study of OMIC claims and make recommendations for improving patients’ ability to fully engage in the informed consent process.

Analysis of informed consent claims

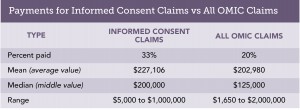

Malpractice claims regularly challenge the adequacy of the consent process. To determine the frequency of these claims and the forces behind them, lawsuits and claims that closed between January 1, 2009, and August 31, 2014, were reviewed. They were classified as “informed consent claims” if the criticism about consent formed an important part of the plaintiff’s case, even if this was not the sole or primary allegation. This contention was found in 54 of the 1305, or 4%, of the reviewed claims. Two claims resulted in plaintiff verdicts and 16 others were settled by OMIC. Defendant ophthalmologists were awarded defense verdicts or granted motions for summary judgment by the courts four times, while 32 others were dismissed by the plaintiff without any payment by OMIC. The table below gives details on the amounts paid to settle these claims and compares  them to OMIC claims overall. Informed consent claims were more successful for plaintiffs than claims overall during the same time period, requiring a payment to resolve them in 33% versus 20% of claims. Moreover, the mean and median payment were both higher for informed consent claims. The most useful part of the claims analysis, however, is the information it provides on the two types of situations most likely to lead to miscommunication about risk.

them to OMIC claims overall. Informed consent claims were more successful for plaintiffs than claims overall during the same time period, requiring a payment to resolve them in 33% versus 20% of claims. Moreover, the mean and median payment were both higher for informed consent claims. The most useful part of the claims analysis, however, is the information it provides on the two types of situations most likely to lead to miscommunication about risk.

Vulnerable patients who accept recommended care

All patients undergoing surgery are at risk for common complications such as infection, hemorrhage, loss of vision, and damage to the eye. Patients with complex histories, or those with comorbid eye or systemic conditions, are often at higher risk. And many of these patients are elderly and non-English speaking, which can increase the obstacles to successful communication as the studies on low health literacy show. The following claims illustrate that plaintiff and defense experts alike criticized insureds for their failure to address additional risk in such patients.

An elderly patient with a history of several surgeries for a pituitary tumor and an increasing cup-to-disc ratio and pale optic nerve presented with a macular hole. The ophthalmologist recommended a vitrectomy. Postoperatively, the patient sustained significant vision loss whose cause was never determined. In his lawsuit for negligence and lack of informed consent, the plaintiff claimed the ophthalmologist assured him that his vision would improve and did not discuss any risks. Moreover, the eye surgeon asked him to sign a generic consent form that listed the type of surgery but did not specify risks either. The plaintiff expert strongly criticized the defendant ophthalmologist for not explaining how the preexisting damage to the optic nerve would exacerbate the effect of any further loss of vision. Defense experts supported the decision to perform surgery but acknowledged that if the plaintiff’s account of the discussion were to be believed, his informed consent had not been obtained. Defense counsel found the plaintiff and his wife to be sympathetic and credible, so the physician agreed with the defense attorney’s advice to settle the case for $250,000.

Another elderly, frail patient who suffered corneal decompensation after a combined cataract and glaucoma surgery testified in her deposition that the physician never told her what procedure he would be doing and never informed her that she had a cataract. She was unable to state, even at her deposition, what surgery had been performed. Plaintiff and defense experts agreed it was not clear that the patient had understood that she was consenting to a combined procedure, much less how having two done at the same time impacted the risk profile of the surgery. Her claim settled with the physician’s consent for $140,000.

A third patient who did not speak or read English did not realize that the consent form he signed was an agreement to participate in clinical research instead of for cataract surgery. When he suffered a series of complications, including capsular tear, a dislocated IOL, and a giant retinal tear, and ended up with NLP vision, he sued. The plaintiff alleged not only lack of informed consent but fraud about the clinical trial. The patient was never enrolled in research and had merely been given the wrong form. The defense was unable to get the fraud allegation and demand for punitive damages dismissed, so the physician agreed to settle the case for $200,000. The informed consent process in these claims was far from ideal. Each time, the patient accepted the information or document provided by the ophthalmologist and followed the recommendation to have surgery without asking questions or raising concerns.

Patients with strong preferences

Unlike the vulnerable patients described above, some patients are clearly engaged in the consent discussion, ask questions, and state their preferences. When those wishes seem to be ignored, they sue. One patient, for example, did not want to wear glasses after cataract surgery and affirmed this goal at each preoperative visit. She took home the procedure-specific consent form to review again. When she read that glasses were often needed after cataract surgery, she called the surgeon, changed the form to cross out that section, and mailed it back to the office. Postoperatively, she not only needed glasses but experienced pain. Efforts to ascertain the cause were in vain, but her vision improved and the pain disappeared after an IOL exchange was performed by another ophthalmologist. The plaintiff expert’s only criticism related to informed consent. Feeling his care was appropriate, the physician refused to settle. During discussions after they had rendered their verdict, members of the jury opined that the surgeon should have noted and addressed the changes to the consent form and that the plaintiff did not get the outcome she wanted. They awarded her $12,916, which covered the cost of the two procedures, and $4,200 for her pain and suffering.

Three additional lawsuits stemmed from a misunderstanding about the need for glasses after cataract or refractive surgery. Four others challenged the consent for monovision. Patients seem to better hear and remember comments that appear to promise benefits. These eight lawsuits show that ophthalmologists need to not only explain risks, but also clarify surgical goals and manage expectations. Eye surgeons should consider postponing or cancelling surgery on patients who are not willing to accept the need for glasses or the possibility of complications. This review of informed consent lawsuits shows that patients who consent to surgery may not understand what they have been told. The Hotline article will explore ways to confirm that key information has been effectively communicated.

- National Patient Safety Foundation. Health Literacy: Statistics at a Glance. http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.npsf.org/resource/collection/9220B314-9666-40DA-89DA-9F46357530F1/AskMe3_Stats_English.pdf. Accessed 11/5/14.