Second cataract surgery proceeds when CRVO goes undetected

RYAN BUCSI, OMIC Senior Litigation Analyst

Allegation

Negligent management of cataract patient resulting in bilateral blindness.

Disposition

Ophthalmologist was dismissed from case and a settlement of $930,600 was paid on behalf of the entity.

A 78-year-old patient presented to a young OMIC insured, who diagnosed bilateral cataracts. The patient paid in advance for the cataract surgeries with a credit card. The first surgery on the left eye was uncomplicated. Hours later, a staff member confirmed via telephone that the patient was doing well. On the postoperative day one examination, neither the patient nor the insured had any concerns. The patient was to return to clinic in one week, the day prior to surgery on the right eye. Although there was no written protocol, it was the insured’s understanding that patients who have eyes operated on one week apart are given a placeholder clinic appointment prior to the second eye surgery. The insured believed the patient was called the day before the second surgery and denied having any problems, so the appointment was cancelled. However, there was no documentation that such a call to the patient ever took place. The insured performed an uncomplicated cataract surgery on the right eye. On postoperative day one, the insured noted that vision in the left eye was virtually gone and diagnosed a central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO). A retina consult confirmed the diagnosis of CRVO and the left eye was injected with Avastin. One week later, the insured examined the patient, who complained of a rapid visual decrease in the right eye. Upon examining the right eye, the insured could actually see the retinal vein occlusion occurring. The insured immediately referred the patient back to the retina specialist, who confirmed the diagnosis of CRVO.

Analysis

The patient and his spouse testified during their depositions that they had reported reduced vision in the left eye to one or more of the intake persons at the surgery center. They were distressed that no one at the surgery center examined the left eye and contended that the surgery center, through its personnel and technicians, deviated from the standard of care by not communicating their complaints to the insured. If staff had relayed the complaint, the plaintiff argued that the insured would have examined the plaintiff’s left eye, diagnosed a developing CRVO, and cancelled the surgery on the right eye. The plaintiff’s argument gained credibility when the insured testified that, even though there was no protocol in place to do so, the patient was asked by multiple staff about the left eye, and had he been informed of any problem, he would have cancelled the surgery. Both the insured and surgery center staff testified that they were not informed of vision loss in the left eye. In order to rule in favor of the plaintiff, a jury would have to believe that an experienced staff failed to inquire about the left eye and pass on the patient’s complaint of visual loss to the ophthalmologist. However, this was a catastrophic injury that occurred in a notoriously plaintiff friendly venue where a jury was more likely to side with the sympathetic plaintiff’s story, so a settlement of $930,600 on behalf of the entity was negotiated.

Risk management principles

Only one postoperative examination occurred prior to proceeding with cataract surgery on the second eye. If another examination had taken place prior to the second surgery, it is possible that some vision loss may have been detected, thus leading to further exploration and cancellation of the second surgery. While the defense argued that the patient and his wife did not report any decrease in vision in the left eye, none of the surgery center employees documented that he was asked about his left eye or complained of decreased vision. The importance of documentation cannot be overstated. A lack of thorough documentation or no documentation negatively affects the defensibility of medical malpractice lawsuits. As mentioned earlier, the patient paid for the procedures using a credit card. After the poor result, the patient disputed the charges with the credit card company and refused to pay the bill. This was not brought to the insured’s attention and the billing department pressed forward with collection. This created even more ill will between the patient and the insured’s office and would have also made the surgery center look unsympathetic in front of a jury. Waiving a bill for services after a poor outcome is something that should be considered and discussed with our risk management or claims department. OMIC welcomes and encourages early reporting of poor outcomes prior to the initiation of litigation.

What’s happening in Wisconsin?

If you haven’t heard the news, we now writing coverage for ophthalmologists in the Badger State! Go here for more information.

If you haven’t heard the news, we now writing coverage for ophthalmologists in the Badger State! Go here for more information.

After working for more than 20 years, OMIC has been successful, working with other insurers and key legislators, in getting changes enacted that will both benefit patients and physicians and medical providers in the state.

We are appreciative of the Wisconsin Office of the Commissioner of Insurance for their efforts in approving OMIC.

Check out the latest news on rates and dividends.

See 20 reasons to be insured by OMIC.

Read the article Wisconsin Allows Risk Retention Groups to Insure Health Care Providers in the recent edition of Captive magazine.

Stories

In a new series, OMIC invites policyholders to tell their stories about what OMIC means to them. We strive to be a great service of the American Academy of Ophthalmology, totally independent, but with a purpose much larger than other malpractice insurance companies. We hope to fulfill a critical role whereby leveraging OMIC’s unique experience in defending ophthalmology we may offer specific advantages an ophthalmologist will not find with other companies.

The Risk Management Lifeline by Ellen Adams

In 2002, I was hired as the Compliance Officer for Ophthalmic Consultants of Boston. With the ink barely dry on my MBA and over 16 years experience as an ophthalmic technician/scrub assistant, I felt ready to handle HIPAA, coding, and OSHA issues. After all, that is what a compliance officer does, right?

How wrong I was. >> more

The Risk Management Lifeline

Ellen Adams

Compliance Officer

Ophthalmic Consultants of Boston

In 2002, I was hired as the Compliance Officer for Ophthalmic Consultants of Boston. With the ink barely dry on my MBA and over 16 years experience as an ophthalmic technician/scrub assistant, I felt ready to handle HIPAA, coding, and OSHA issues. After all, that is what a compliance officer does, right?

How wrong I was.

Almost immediately, I found myself in the cross hairs. Patients with complaints were transferred to me. I answered calls from lawyers asking for copies of medical records. And our satellite office managers called me whenever problems arose, such as when a patient fell in the parking lot. In most of these situations, no one really knew what to do and panic was often coloring the event.

After one especially concerning situation, I met with OCB’s then-president, Dr. Tom Hutchinson, to ask for help. Without hesitation, his response was to call the OMIC hotline. At the time, I didn’t realize there was such a thing, but over the past 11 years this service has become one of my most valuable tools. Most importantly, I have found that there is no need to panic. I have objective, highly knowledgeable experts when I need them; a lifeline that is just an email or phone call away.

One recent typical day at OCB found me working at my desk when the phone rang. It was a patient who at first seemed reasonable. We were about six months into using electronic health records, and she was upset that a note by one of our physicians included an unflattering comment about how demanding she was. She was particularly concerned that her primary care physician would be able to see the comment and wanted it removed.

What the patient did not realize was that the note she had seen during her previous visit had not been finalized; the draft version had been subsequently reviewed by our physician and this particular comment had been removed. While speaking with her, I reiterated several times that the final version of the note in her record did not contain the comment, but that was not good enough for her and the conversation continued to escalate into a highly charged tirade.

As the call approached 45 minutes, I realized this patient was not as she had first presented on the phone—in fact, I was beginning to suspect that our physician’s now removed comment was closer to the truth. She was unreasonable, demanding, and unpredictably volatile. Time for a lifeline!

I emailed OMIC and asked for help. Not only did OMIC’s risk manager, Anne Menke, assure me that neither I nor our practice was the problem, she also guided me through a reasonable response to the patient. When that didn’t work (a subsequent hour and twenty five minute phone call with the patient days later progressed in a similar fashion as the previous encounter), OMIC helped me draft a letter to discharge the patient from our practice. Clearly, this was in the best interest of both the patient and OCB.

OMIC’s help was exactly what I needed in order to facilitate a solution to a difficult practice-patient relationship while also protecting our practice. Incredibly, when the patient called back a full year later wishing to be seen again by OCB, I was back on the phone with Anne, who recalled the entire incident and helped me compose a “discharge means discharge” letter to the patient.

This is what I value most about OCB’s relationship with OMIC. The risk managers are there to help me. They treat my calls as completely confidential. No one, not even other employees within OMIC, have access to risk management files and they keep detailed notes so anyone can pick up the tale if things escalate; they are calm and rational when patients pull me into an abyss. They are my lifeline.

The OMIC risk management team has given me the confidence and tools to now handle most situations on my own. They use hotline calls like mine to develop recommendations, protocols, sample letters, and consent forms, which are posted on the OMIC website so they are available when I need them.

When I call the hotline now, my OMIC team lets me know if my new problem is indeed unique or scarily interesting. I feel like OMIC is not just another malpractice insurance company but an integral part of my compliance and risk management team.

2015 Claims Study: Giant cell arteritis claims are costly and difficult to defend

RONALD W. PELTON, MD, PhD, OMIC Committee Member, and ANNE M. MENKE, RN, PhD, OMIC Risk Manager

A 77-year-old male patient presented for the first time to our insured ophthalmologist to report the sudden onset of intermittent diplopia six days prior and a headache over his eyebrows for one day. Noting right inferior oblique muscle paresis but unable to determine its cause, and with no neuro-ophthalmologist in the region, the eye surgeon referred the patient to a neurologist. The patient told the neurologist that the headache had actually lasted for one month and that he was also experiencing jaw pain. This additional information prompted the neurologist to include giant cell arteritis (GCA, also known as temporal arteritis) in the differential diagnosis and to order an MRI, CT, and lab work.

When the patient saw the ophthalmologist about two weeks later, he reported a new symptom, a low-grade fever, with ongoing headache and diplopia. Five days after that—a full three weeks after the initial visit to the ophthalmologist—the patient lost vision in his left eye. An emergency room physician diagnosed giant cell arteritis and began intravenous steroid treatment, but the patient never regained vision in that eye. The malpractice lawsuit against the ophthalmologist settled for $85,000; we do not know the outcome of the suit against the neurologist.

Armed with hindsight bias, the classic signs and symptoms of giant cell arteritis jump out: older patient, vision changes, headache, jaw pain, and fever. It is hard to imagine how the definitive diagnosis and treatment were delayed for so long and easy to erroneously conclude that both physicians must have been incompetent. The claims investigation showed instead that these physicians had treated patients with giant cell arteritis, knew its signs and symptoms well, and understood that emergent treatment is needed to prevent imminent, bilateral vision loss. What, then, led these physicians astray?

Severe vision loss, costly claims

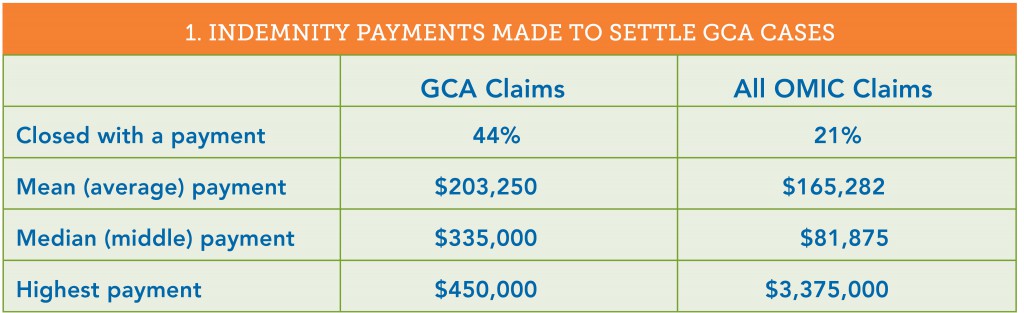

This issue of the Digest will report on a study of OMIC claims involving 18 patients diagnosed with GCA between 1993 and 2014. In 12 of the 18 cases (66%), no physician included GCA in the differential diagnosis. Four of these patients were seen only by an ophthalmologist; the rest were examined by an eye surgeon and one to three additional physicians. And although GCA was considered by the ophthalmologists in each of the remaining six cases, symptoms in five patients progressed when either the ophthalmologists or other physicians did not follow through to confirm the diagnosis and coordinate treatment. All 18 patients experienced severe vision loss, often bilaterally. OMIC had to settle twice as many of these claims as OMIC claims overall, and the mean and median payments were both considerably higher (see table 1).

The short window for diagnosis and treatment and the risk of severe bilateral vision loss make the high stakes of this relatively rare condition clear. This issue of the Digest will explore the reasons for these poor outcomes, the standard to which medical experts hold physicians who treat these patients, and the measures ophthalmologists can take to improve the likelihood of a correct and timely diagnosis.

Patients presenting with only visual problems

Giant cell arteritis, a systemic inflammation of the blood vessels that restricts blood flow causing organ and tissue damage, most commonly affects patients over the age of 50. In addition to the symptoms noted above and scalp tenderness, varied and non-specific constitutional symptoms, such as fatigue, malaise, and weight loss, may develop over time. It can be difficult to diagnose GCA when the only symptom is a change in vision. Four of the 18 patients presented this way. In two of these cases, defense experts supported the ophthalmologists’ care and the claims closed without payment, even though the insureds did not diagnose GCA or such diagnosis was delayed. In one case, a patient with dense cataracts that explained her vision loss was appropriately referred for work-up of a choroidal mass; the jury returned a defense verdict. In the second case that closed without a payment, a patient who presented with intermittent blurry vision was diagnosed with amaurosis fugax, a temporary loss of vision in one eye caused by a lack of blood flow to the retina. Because the patient was 79, the ophthalmologist ordered an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). When the result was normal at six, he repeated the test and got the same result. He diagnosed GCA six days later when the patient complained of a shade over the eye and developed a Marcus Gunn pupil and visual field deficit. OMIC declined the patient’s settlement demand and the case was ultimately dismissed. The two other cases where vision change was the only symptom were settled when OMIC could not find supportive defense experts. In one, the ophthalmologist noted papilledema in an 81-year-old who presented with sudden vision loss, but he did not work up its cause. The case settled for $275,000. In the other, the ophthalmologist was criticized for not clarifying the nature of the visual complaint. The 82-year-old patient had written on the history form that her vision “blacked out.” The surgeon did not read the form and documented only “blurry vision” and diagnosed her with visual migraine. The case settled for $350,000.

Problems eliciting a thorough and accurate history

Exploring the precise nature of the vision change would have helped another ophthalmologist entertain a GCA diagnosis. His patient complained of a headache for two days and a “curtain,” which he understood to be transparent. It was only during the investigation of the lawsuit that he learned the patient had experienced a “dark” curtain that caused frank vision loss. He felt, in retrospect, that the combination of vision loss and headache in an elderly patient should have alerted him to GCA and agreed to settle the claim for $100,000.

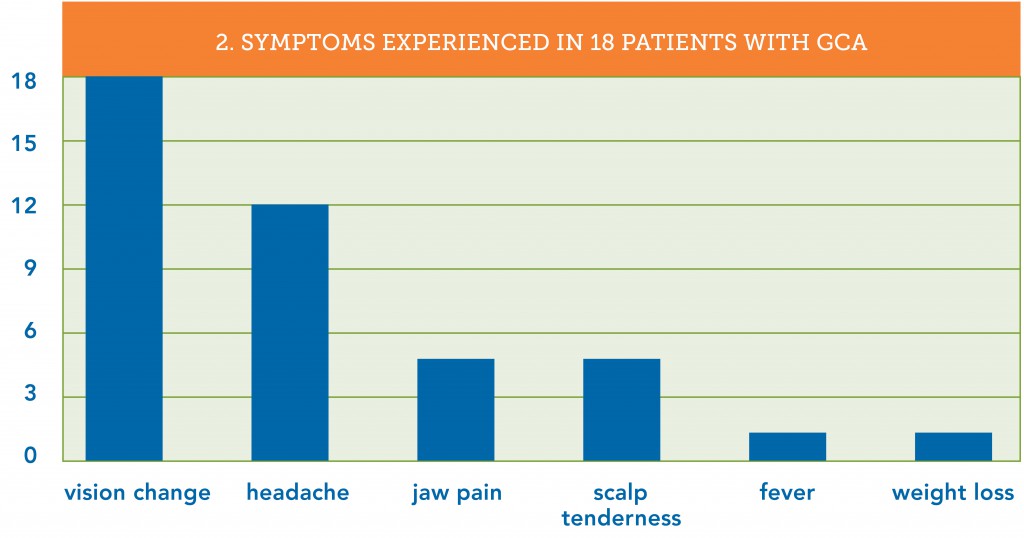

While it is important to get accurate information about the eye complaint, it is crucial to query older patients about constitutional symptoms. A careful review of signs, symptoms, and systems can help distinguish the few patients who could have GCA from the large number of older patients with eye problems seen daily in ophthalmic practices. Which symptoms did the patients in our study exhibit? Consistent with GCA’s usual appearance in patients over 50 years old, those in this study ranged from 62 to 86. As part of a claims investigation, defense attorneys obtain and review all of the patient’s medical records. These reviews revealed that 15 of the 18 patients (83%) were experiencing GCA symptoms other than vision changes at the time of their initial visit to the ophthalmologist. Of these 15 patients, 12 reported headaches and 7 of the 12 had additional symptoms (see table 2).

The ophthalmologists, however, failed to elicit the non-vision-related symptoms in 10 of the 15 patients (66%) who were having them. Defense experts opined that this inadequate history contributed to the delay in diagnosis and was below the standard of care. The ophthalmologist in the claim described in the beginning of this article learned only of the vision complaints and headache, while the neurologist, who saw the patient near the same time, elicited the duration of the headache and the existence of jaw pain. Ironically, the ophthalmologist testified in his deposition that he did not consider GCA in his differential diagnosis since the patient did not complain of jaw pain. He did not explain why he relied upon the patient to offer this information instead of asking for it.

Why is obtaining an accurate history so difficult? First, patients often report their history differently to each healthcare provider based upon the questions asked and the time spent gathering the information. Often it was other physicians who obtained a more thorough history, but in two of our claims, the ophthalmologists’ staff members obtained and documented the presence of GCA symptoms. Not only did the ophthalmologists not get the same information when questioning the patients a few minutes later, they also did not review the notes made by their staff members. This lapse was criticized by defense experts and contributed to the decision to settle these claims. Second, patients presenting with eye complaints often do not think that it is important or pertinent to tell their ophthalmologist about non-ophthalmic problems they are experiencing. More than in most diseases, however, prompt diagnosis of GCA depends upon the thoroughness and accuracy of the health history. In each of the 15 claims where patients had more than just visual symptoms, the plaintiff expert alleged that the diagnosis could have been made earlier if the ophthalmologist had obtained a more thorough history. Ophthalmologists examining older patients, especially those with vision changes and headache, need to take a more active role in obtaining the history. Dr. Ron Pelton, a practicing oculofacial surgeon who serves on OMIC’s claims and underwriting committees, has developed a GCA checklist to prompt ophthalmologists to ask key questions and document both positive and negative findings. It can be found at Giant Cell Arteritis Checklist.

Missed opportunities

So what happened in the first case? While the ophthalmologist did not elicit a thorough history or include GCA in his differential diagnosis, the neurologist to whom he referred the patient did ask the appropriate questions. The combination of diplopia and pain in the temporal mandibular joint led the neurologist to a robust differential diagnosis, which included right fourth nerve palsy versus right inferior oblique paresis, brain stem ischemia, myasthenia gravis, and vasculitis. He appropriately ordered an MRI, CT scan, and laboratory work, including an ESR. About a week after he examined the patient, the neurologist realized that the lab had mistakenly not performed the ESR. He mailed the patient a prescription to have it done the next day but the patient never went. Six days later, the patient brought the results of the MRI, CT, and lab work (minus any ESR results) to his second visit with the ophthalmologist, who skimmed the report, which discussed the non-specific MRI and CT results and the normal lab results. He failed to notice that the lab had not performed the ESR. While he did see that the patient had been given a prescription to have the ESR repeated six days prior, he assumed the test had been done and was again normal. The ophthalmologist advised the patient to keep his follow-up appointment with the neurologist in four days time. Experts who reviewed the claim felt that four opportunities for an earlier diagnosis that would have preserved the vision had been lost: when the lab did not perform the first ESR ordered, when the patient did not go back to get the ESR lab test done, when the neurologist did not follow up to ensure it was done, and when the ophthalmologist failed to note the lack of ESR results. Had the ophthalmologist asked the patient, he would have learned that no ESR had been done. This information, combined with the new symptom of fever, could have prompted him to consider GCA and order a stat ESR.

Preventing vision loss

This constellation of incomplete history, poor coordination of care among physicians, and problems with patient adherence occurred in many of the claims, including the one in the Closed Claim Study. This article provides information on actions ophthalmologists can take, such as proactively obtaining a more thorough history, to improve the likelihood of including GCA in the differential diagnosis when older patients present with vision changes. The checklist created by Dr. Pelton can prompt such questions and help track the completion of key tests and consults. A robust appointment and test tracking system plays a pivotal role in preventing diagnostic error (see “Test Management System is Key to Prompt Diagnosis” and “Noncompliance” at www.omic.com for advice on how to implement one). The Hotline article in this issue provides recommendations on ways to improve communication with other physicians and your staff.