Young ophthalmologists on trial

PAUL WEBER, JD, OMIC Vice President, Risk Management/Legal

PAUL WEBER, JD, OMIC Vice President, Risk Management/Legal

For a physician, it is not a matter of if but when you are going to incur a malpractice claim. Over the course of a 35-year career, 95% of ophthalmologists will have at least one claim against them and more than half can expect two or three.

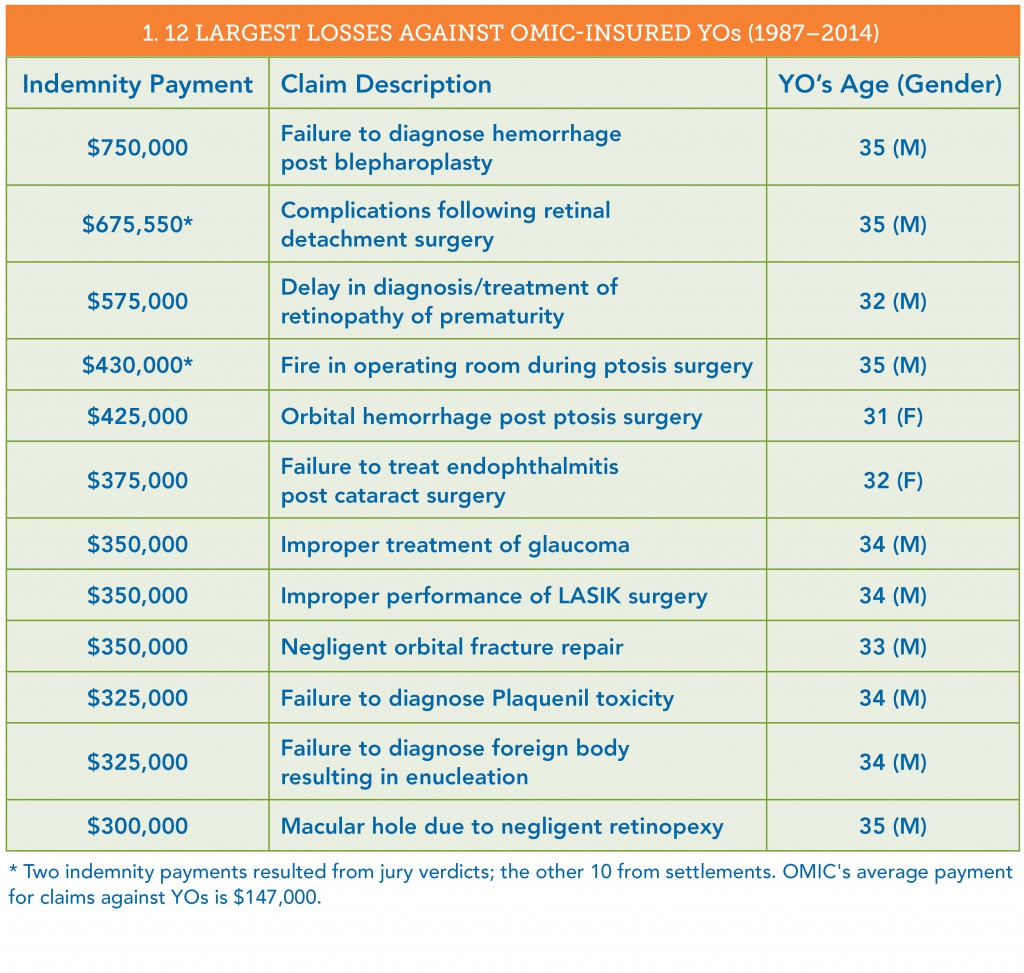

Since 1987, OMIC has closed more than 400 claims brought against young ophthalmologists (YOs) (see Table 1).

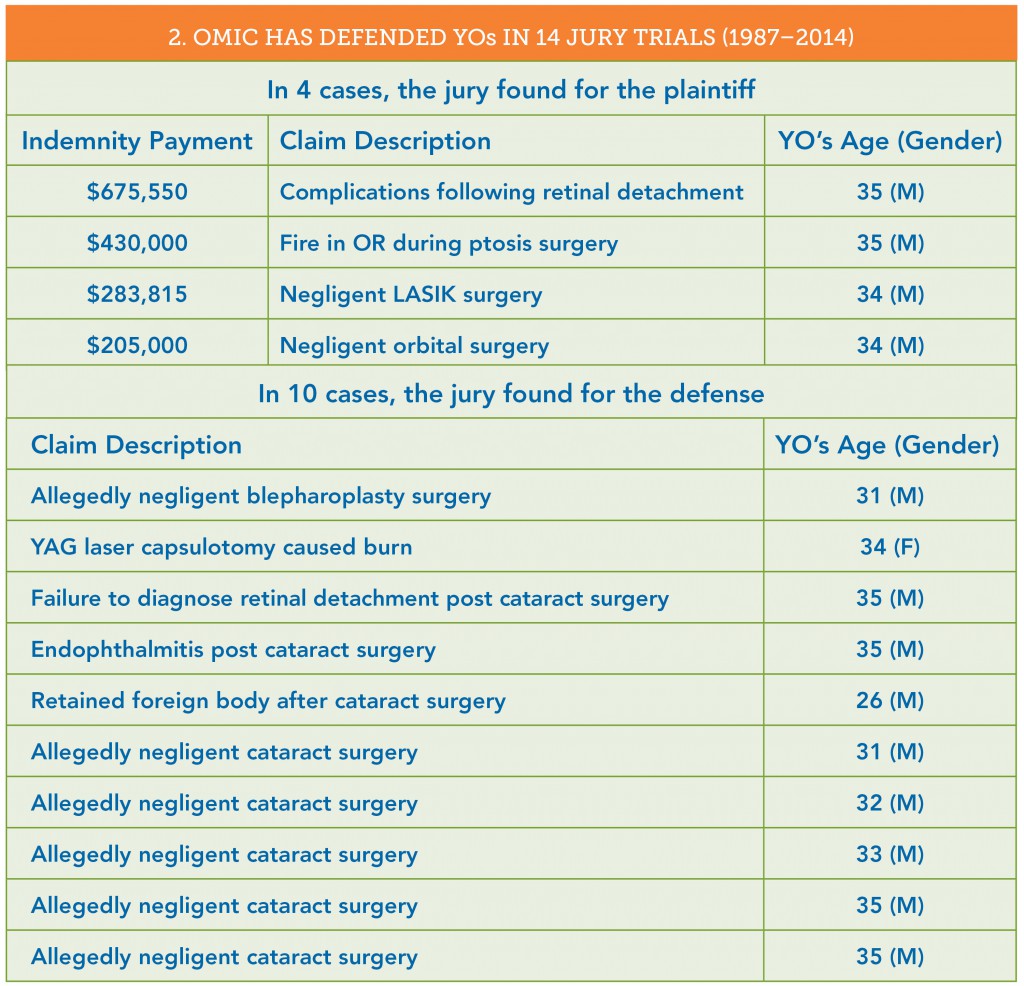

- 14 of these claims went to a jury trial; the jury found for the plaintiff in 4 cases and for the defense in 10 (see Table 2).

- 20% of these claims were settled out of court with an indemnity payment to the plaintiff.

- 80% of these claims—many of which were found to be without merit—were closed with no payment. In 15% of the cases, there were not even defense costs associated with the claim.

The cases that follow will help you understand some do’s and don’ts to minimize the risk of serious litigation.

A $750,000 payout

The largest loss in a claim against an OMIC-insured YO was $750,000 for failure to diagnose a hemorrhage that resulted in eventual blindness (no light perception) in the patient’s left eye following a bilateral blepharoplasty.

The plaintiff initially focused on the insured’s lack of experience because this was the first blepharoplasty he had performed since his residency. The plaintiff’s lawyer was prepared to suggest that the YO lacked the requisite skill and experience and thus contributed to causing the hemorrhage and poor postoperative care.

The real problem was the patient’s chart. First, the YO did not document visual acuity on the first postop visit on August 21, five days after surgery. (The patient later testified that she was “blind” in her left eye at that visit.) The patient never returned to the YO. She went to another ophthalmologist a week later on August 28 and was found to have light perception only in the left eye.

What made this case indefensible occurred on September 5. After learning that the patient was blind, the insured began “supplementing” the patient’s medical record. First, he changed and added information to his original preop note concerning informed consent. The original note read “Discussed risks, benefits, and alternatives of bilateral blepharoplasty. She agrees and wants it done.” The new note, written several weeks later, read “Discussed risks, benefits, and alternatives of bilat bleph in detail. She agrees and wants it done. We discussed no ASA, blood thinners, garlic, Vit. E, red wine for two weeks before procedure. She understood.”

There also was a late dictated chart entry for the August 21 postop visit. On that day, after the postop visit had taken place, the physician apparently called his technician and asked her to make an entry in the patient’s chart. He later added his own note on September 5. Unfortunately, the two notes were inconsistent in that the insured’s own note stated he performed an optic nerve and retina exam, but the earlier dictated note did not. The plaintiff claimed that all the changes to the medical record were self-serving and the insured was trying to “cover himself.”

Trouble at the deposition

Before trials take place, attorneys can question litigants and other important witnesses during a deposition. This allows both sides to gather evidence for the trial. The witnesses are under oath, and a court reporter transcribes the testimony, which is sometimes videotaped. In this case, when the YO was being examined at his deposition, he became very flustered and had great difficulty answering questions. When asked whether it was important to keep medical records for the health and safety of the patient, he answered “No.” When asked whether it was important to keep accurate and complete medical records, he first answered “No,” and then “It depends on the circumstances.” He stated that he had supplemented the record to make it more “clear” to him. It is quite possible that he made the changes to more accurately reflect what he did and said at those office visits, but the plaintiff’s attorney would paint the changes in the worst possible light. With the consent of the insured, OMIC settled the case prior to trial.

Changing documentation is problematic. When you have had a bad outcome or serious complication, beware of supplementing or adding to your prior notes. Sometimes changes must be made after these events because you don’t want inaccurate or incomplete information being sent and relied upon by subsequent providers. When these situations arise, you should get advice—call OMIC, your malpractice insurance company, or your personal attorney.

Voices of experience

OMIC insureds who have been through litigation offer this advice:

- Maintain absolute integrity of the medical records.

- Document all phone calls.

- Have a session with staff about the importance of charting no shows.

- Start charts with ER call. Contact patients if they fail to show.

- Rely less on staff to ensure documents are properly executed.

- Document that no guarantee was made regarding outcome.

- Have longer preop discussions.

- Be open with patients about complications.

- Use procedure-specific consent forms.

Informed consent is critical

Every surgical procedure requires informed consent. Although all of the following four cases involving cataract surgery resulted in a verdict for the defense, they demonstrate that informed consent is more than just having a patient sign a form.

Case 1: Plaintiff expert was critical of the fact that the physician performed the procedure without informing the patient of the minimal benefits anticipated from the surgery. The patient had a history of glaucoma, a small and poorly dilated pupil, and a branch retinal vein occlusion.

Case 2: Plaintiff expert stated that it was below the standard of care to not advise the patient that he had lattice degeneration and that this increased the risk of retinal detachment. There was no note in the chart regarding an informed consent discussion.

Case 3: Plaintiff expert stated that the physician should have informed the patient that he was a relatively new ophthalmologist and had not performed cataract surgeries outside of his residency program.

Case 4: Plaintiff expert testified that the physician did not properly provide informed consent because he did not provide alternatives, and that there should have been a consent form in the chart signed by the patient.

Key steps for informed consent

It is certainly important to have a patient sign a procedure-specific informed consent document, but there are other steps you should consider.

Document your discussion with the patient. This should include:

- Time. Note the specific amount of time you spent with the patient (or his or her guardian/caregiver) explaining the risks, benefits, and alternatives.

- Who was present. Note who was in the room when you had this discussion (e.g., patient’s spouse, adult child, your staff).

- Who translated. If the patient’s English is limited, document who was translating.

- Comprehension. Note how you determined that the patient actually understood what you discussed (e.g., the questions used to determine comprehension).

Document what information you provided. Document that you gave a copy of the signed consent form to the patient. You also should document when you provide patient education materials (e.g., fact sheets) or when the patient views videos.

Document your informed consent process/protocol. Have a meeting with your staff to review and document the steps that are taken for informed consent. Save this written process/protocol, use it to orient new staff, and revise it as needed.

Create a checklist. Some physicians write down the issues that they always discuss with patients prior to a procedure and use this as a checklist. The checklist gets entered in the patient’s chart. Take advantage of OMIC’s guidance on informed consent available at www. omic.com/informed-consent obtaining-and-verifying/.

Emotional impact of a claim

Regardless of whether they win or lose a lawsuit, physicians who are sued are at risk of severe emotional distress. Resources to deal with the anger and other difficult emotions that might arise during and after litigation may be found on OMIC’s website at www.omic.com.

A malpractice lawsuit can be emotionally traumatic, but physicians eventually see their cases through and often emerge stronger and even more committed to their chosen profession:

“I was able to get through this horrific ordeal relatively unscathed, but a bit stronger from my scars. The

phone call I received informing me that my case had been dismissed ranks, in terms of emotional impact, just below that of my children being born.”

“I am humbled at the experience I have gone through during the four-year process. I am grateful to be insured by OMIC and to have the representation that I had to help resolve the case prior to trial. I hope to be able to share my experience with others so that they understand that, while frustrating, the process works.”

“It was a very stressful experience, but I am a wiser doctor for having gone through it.”

This article was first published in EyeNet Extra: A Guide to Practice Success (August 2015), a supplement written specifically for young ophthalmologists.

Message from the Chair: Swan Song

TAMARA R. FOUNTAIN, MD, OMIC Board of Directors

Do you know the origin of the term “swan song,” defined by Webster as a farewell appearance or final act or pronouncement? According to Greek mythology, swans, while revered for their graceful beauty, were not considered capable song birds until, peculiarly, they were near death. It was only then that they were said to produce their most hauntingly beautiful arias. I am not near death (far as I know), am not retiring from practice (that, I know) nor do I sing (well), but I am approaching the culmination of my OMIC service and this is my final message to you as Chair of the Board.

Do you know the origin of the term “swan song,” defined by Webster as a farewell appearance or final act or pronouncement? According to Greek mythology, swans, while revered for their graceful beauty, were not considered capable song birds until, peculiarly, they were near death. It was only then that they were said to produce their most hauntingly beautiful arias. I am not near death (far as I know), am not retiring from practice (that, I know) nor do I sing (well), but I am approaching the culmination of my OMIC service and this is my final message to you as Chair of the Board.

As of December 31, I will have served the maximum 15-year term on OMIC’s Board and committees. I was part of an experiment (not since repeated, I will add) when, as a member of the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Young Ophthalmologist Committee, I was tapped to fill a vacant OMIC committee spot back in 2000. I was barely out of fellowship, knew little about malpractice insurance—except that I had to have it to see patients—but saw the opportunity in this stretch assignment and accepted the invitation without reservation.

It is no small irony that this final Chair Message comes in a Digest dedicated to the young ophthalmologist—those in residency, fellowship, or their first five years in practice. This generation of doctors may look different (less white, more female), learn differently, and have different career expectations, but their liability exposure remains the same as when mid-career and senior ophthalmologists started out. A sobering 95% of us will be named in a lawsuit over an average 35-year career. It is never too soon to promote risk management strategies to those who are just beginning their practice. OMIC is committed to supporting young ophthalmologists as it is they who will carry the torch of ophthalmic advocacy, education, and patient care into this new millennium.

I am passing the Chair baton to my colleague, mentor, and friend, George A. Williams, MD. George has forgotten more than I will ever know about the world of ophthalmology. He will bring considerable expertise in finance, regulatory affairs, and single malt Scotch to continue the tradition of strong leadership and management that has become the hallmark of the OMIC brand.

It has been particularly emotional for me to approach my final days on this Board, an association of people that has become like another family to me. No one succeeds in chairing such an exemplary body without a whole lot of support. To Board members past and present who saw something in me I didn’t see myself, to our consultants who took me under their wing in what I like to call my own OMIC “home-schooling,” to the dedicated staff at the mothership in San Francisco who always answered my late-night emails, my last minute requests and were my own squad of cheerleaders, and to our beloved CEO Tim Padovese, the executive captain of the OMIC ship, you’ve all shaped me in profound ways both personal and professional. Thank you for this improbable and glorious ride.

New regulatory and cyber (eMD) liability benefits

We are pleased to announce that four new coverage benefits are being added to your professional liability policy effective January 1, 2016. Enhancements include Proactive Privacy Breach Response Costs and Voluntary Notification Expenses, which allow insureds an opportunity to take preemptive actions to avoid adverse situations prior to legal requirements to do so; BrandGuard™, which provides reimbursement for lost revenue directly resulting from an adverse media report or notification to patients regarding security or privacy breaches; and PCI DSS Assessment coverage to pay fines or penalties levied by the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standards Council (for VISA, MC, AmEx, Discover, and JCB merchants who are not PCI DSS compliant). Policyholders can learn more about these and other OMIC benefits at http://www.omic.com/policyholder/benefits/.

Coverage for regulatory and cyber electronic media (eMD) exposures is included in OMIC’s standard professional liability policy at no additional premium, subject to a per policy period sublimit of $100,000 per claim and in the aggregate. The sublimit for disciplinary proceedings related to direct patient treatment is $25,000.

Congratulations to the winner

Thank you to everyone who connected with us during the annual meeting of the American Academy of Ophthalmology in Las Vegas, Nov. 14–17, 2015. We had more than 1,200 people attend our seminars, events, and exhibit booth. Thank you for your support and for another great year of accomplishments. A special congratulations to Dr. Michelle Boyce of Kansas, who was the winner of our drawing for an iPad Pro! Dr. Boyce is a resident in the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

YO news

Ophthalmologists in their early years of practice are encouraged to connect with us on the YO News page at http://www.omic.com/partners/yo-news/. You will find resources designed specifically for young ophthalmologists and links to our social media community pages. Events that OMIC has sponsored in the past, such as the YO Global Reception and YO Lounge instructional courses, are also highlighted.

What may I safely delegate?

ANNE M. MENKE, RN, PhD, OMIC Risk Manager

Young ophthalmologists often join established practices. Non-physician staff at these practices may include licensed team members, such as registered nurses and optometrists, or unlicensed staff, such as technicians and assistants. Young ophthalmologists have called our Hotline worried about over-delegation as well as puzzled when their delegation decisions are seen as risky.

Q Who determines what physicians may delegate?

A What physicians may delegate is part of the “practice of medicine” as defined in each state’s medical practice act and clarified in regulations. Licensed staff have their own legal scope of practice and can contact their licensing board if they are not sure if they may perform certain tasks. Sometimes, even after researching state laws and regulations, you may not be sure of what medical tasks you may delegate to non-physicians. Use the training, licensure/certification process, state law, and the principles discussed in this article to develop protocols that will keep you, your patients, and your staff safe, and improve the defensibility of care rendered under your supervision. Remember the general rule that you may always delegate tasks, but as a physician, you cannot delegate responsibility. The staff members performing tasks on your behalf represent your professional and clinical decisions, and thus, their actions reflect the way you are delivering care to patients.

Q May I delegate prescriptive authority to my staff?

A Yes, but only to certain staff members. Each state limits the ability to write prescriptions to licensed healthcare personnel and provides a “sliding scale” of authority. MDs and DOs are at the top of the scale; with the proper Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) approval for controlled substances, they have unlimited prescriptive authority to order FDA-approved drugs and devices. All other licensed healthcare providers have restrictions. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners may prescribe only medications normally used by their supervising physician that are also listed in the formulary that comprises part of the standardized protocols directing their actions. In some states, optometrists with special training and licensure have limited prescriptive authority. Unlicensed staff, even if certified, may not prescribe drugs or make any decisions about them.

Q What role may unlicensed staff play in computerized drug order entry systems?

A Physicians in some offices use scribes to document their care and orders and instruct them to enter a medication order into the electronic medical record or drug order entry system. In offices with no physician assistant or nurse practitioner, only an ophthalmologist may prescribe drugs or direct a scribe to enter an oral order into the medical record or computerized physician order entry system. The physician must clearly specify the drug and dosage and is responsible for the appropriateness and accuracy of the “scribed” order. To ensure patient safety and limit liability risk, staff should be instructed to read back each order.

Q Who may determine if a patient is a candidate for a cosmetic medical procedure? Who may perform the procedure?

A It takes considerable knowledge and judgment to determine the cause of presenting complaints, what treatment is indicated, if any, and whether the findings from the patient’s history or examination signal increased risk or constitute contraindications. In other words, assessing patients to determine candidacy is the practice of medicine. Nearly all states have legal mechanisms for registered nurses to perform tasks that are considered the practice of medicine, such as Botox injections and some types of laser surgery. With sufficient training and the appropriate standardized protocols that delineate indications, contraindications, treatments, and consultation requirements, registered nurses may usually elicit the history, perform the initial examination, and discuss a proposed course of treatment with the patient as a prelude to presenting their recommendations to the supervising physician. If the physician approves the patient’s candidacy and orders the treatment or series of treatments, the registered nurse may implement the order. Unlicensed staff, even if certified, may not determine candidacy. Contact OMIC’s confidential Risk Management Hotline to determine if you may delegate cosmetic medical procedures to unlicensed staff.

Second cataract surgery proceeds when CRVO goes undetected

RYAN BUCSI, OMIC Senior Litigation Analyst

Allegation

Negligent management of cataract patient resulting in bilateral blindness.

Disposition

Ophthalmologist was dismissed from case and a settlement of $930,600 was paid on behalf of the entity.

A 78-year-old patient presented to a young OMIC insured, who diagnosed bilateral cataracts. The patient paid in advance for the cataract surgeries with a credit card. The first surgery on the left eye was uncomplicated. Hours later, a staff member confirmed via telephone that the patient was doing well. On the postoperative day one examination, neither the patient nor the insured had any concerns. The patient was to return to clinic in one week, the day prior to surgery on the right eye. Although there was no written protocol, it was the insured’s understanding that patients who have eyes operated on one week apart are given a placeholder clinic appointment prior to the second eye surgery. The insured believed the patient was called the day before the second surgery and denied having any problems, so the appointment was cancelled. However, there was no documentation that such a call to the patient ever took place. The insured performed an uncomplicated cataract surgery on the right eye. On postoperative day one, the insured noted that vision in the left eye was virtually gone and diagnosed a central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO). A retina consult confirmed the diagnosis of CRVO and the left eye was injected with Avastin. One week later, the insured examined the patient, who complained of a rapid visual decrease in the right eye. Upon examining the right eye, the insured could actually see the retinal vein occlusion occurring. The insured immediately referred the patient back to the retina specialist, who confirmed the diagnosis of CRVO.

Analysis

The patient and his spouse testified during their depositions that they had reported reduced vision in the left eye to one or more of the intake persons at the surgery center. They were distressed that no one at the surgery center examined the left eye and contended that the surgery center, through its personnel and technicians, deviated from the standard of care by not communicating their complaints to the insured. If staff had relayed the complaint, the plaintiff argued that the insured would have examined the plaintiff’s left eye, diagnosed a developing CRVO, and cancelled the surgery on the right eye. The plaintiff’s argument gained credibility when the insured testified that, even though there was no protocol in place to do so, the patient was asked by multiple staff about the left eye, and had he been informed of any problem, he would have cancelled the surgery. Both the insured and surgery center staff testified that they were not informed of vision loss in the left eye. In order to rule in favor of the plaintiff, a jury would have to believe that an experienced staff failed to inquire about the left eye and pass on the patient’s complaint of visual loss to the ophthalmologist. However, this was a catastrophic injury that occurred in a notoriously plaintiff friendly venue where a jury was more likely to side with the sympathetic plaintiff’s story, so a settlement of $930,600 on behalf of the entity was negotiated.

Risk management principles

Only one postoperative examination occurred prior to proceeding with cataract surgery on the second eye. If another examination had taken place prior to the second surgery, it is possible that some vision loss may have been detected, thus leading to further exploration and cancellation of the second surgery. While the defense argued that the patient and his wife did not report any decrease in vision in the left eye, none of the surgery center employees documented that he was asked about his left eye or complained of decreased vision. The importance of documentation cannot be overstated. A lack of thorough documentation or no documentation negatively affects the defensibility of medical malpractice lawsuits. As mentioned earlier, the patient paid for the procedures using a credit card. After the poor result, the patient disputed the charges with the credit card company and refused to pay the bill. This was not brought to the insured’s attention and the billing department pressed forward with collection. This created even more ill will between the patient and the insured’s office and would have also made the surgery center look unsympathetic in front of a jury. Waiving a bill for services after a poor outcome is something that should be considered and discussed with our risk management or claims department. OMIC welcomes and encourages early reporting of poor outcomes prior to the initiation of litigation.