Call early, call often: Benefits of proactive incident reporting

PAUL WEBER, JD, VP, OMIC Risk Management/Legal, and MICHELLE PINEDA, MBA, OMIC Risk Management Specialist

OMIC handles hundreds of claims and lawsuits every year. However, many insureds are unaware of the additional benefits and services beyond claims handling that OMIC provides to policyholders and their staff. Over the past five years, OMIC has spent more than $1.8 million to help insureds proactively manage a myriad of sensitive, complex liability issues that were not malpractice claims. This Digest reviews some of these events and the value of calling OMIC early and often when they occur.

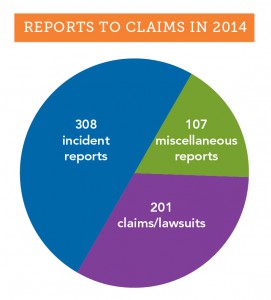

Reports to claims department

In 2014, OMIC’s claims department received over 600 reports from insureds. Of these, 201 were claims

(written demands for money) and lawsuits, and the rest were incident and miscellaneous reports (see graph). Most of the 415 incident and miscellaneous reports were what OMIC considers “potential claims,” events that may result in an actual claim or lawsuit. Such events include oral demands for money or services, medical records requests, adverse outcomes resulting from patient treatment, and other signs the patient may be dissatisfied with treatment. An early call to OMIC’s claims staff starts the process of coverage for a potential claim. Staff will provide guidance on steps to take to minimize the impact of the incident. Some incident and miscellaneous reports don’t fall clearly into the potential claim category. As illustrated in the case study that follows, these matters may arise in an unusual manner and require significant claims and legal assistance before they are resolved.

OMIC insureds are encouraged to contact the claims department whenever they are requested to give their deposition in a malpractice claim so OMIC can determine whether counsel should be assigned. Generally, they are simply being deposed as a “fact witness,” someone who was a treating physician or consultant in the plaintiff’s care. In these cases, OMIC may assign counsel to make sure the insured’s testimony is limited to “facts” and does not include conjecture.

In May 2013, an insured contacted the OMIC claims department thinking he was going to be deposed simply as a fact witness (consulting doctor) in a lawsuit against another physician and a hospital. The plaintiff had undergone gastric bypass surgery. In the weeks following the surgery, the plaintiff was seen at the emergency department several times for nausea and vomiting. During one of these visits, the patient complained of blurry vision, confusion, low energy, and cognitive problems and was admitted to the hospital for further examination. The patient’s gastric bypass surgeon and an internal medicine physician were supervising her care, and the OMIC insured was called to consult on the vision problems. The ophthalmologist felt the patient’s blurry vision could be caused by a thiamine (B1) deficiency. As another physician had already ordered B1 and B6 testing, the ophthalmologist felt his consult report properly communicated his concern to the team of doctors caring for this patient. Unfortunately, none of the treating physicians reviewed the B1 test results, and about five days after the ophthalmology consult, the patient went into a catatonic state and was transferred to a psychiatric hospital. It was only then that the B vitamin test results were interpreted and the patient was noted to be suffering from an extremely low vitamin B1 level. She was diagnosed with Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome and given thiamine to treat the condition. The lawsuit against the surgeon and internist alleged delayed/missed diagnosis and failure to treat, which caused neurological injuries and permanent irreversible brain damage.

OMIC’s claims staff reviewed the notice of deposition and contacted local defense counsel, who determined that the plaintiff attorney might name the insured in the lawsuit. State law allowed the plaintiff six months after the notice of deposition to add defendants. The OMIC defense attorney carefully prepared the insured for his deposition, with the assumption that the insured might be named as a defendant. Accordingly, the attorney attended the depositions of other parties and witnesses to prepare to defend the insured if needed. During the deposition, the plaintiff attorney asked probing questions of the insured’s care, suggesting there should have been better follow-up. The plaintiff attorney also tried to get the insured to criticize the care of the defendants. Fortunately, the insured was well prepared, confidently explaining his own care without giving damaging testimony against the other providers. The OMIC insured was never named as a defendant. His call for deposition assistance limited his role in the lawsuit, ultimately protecting him and keeping OMIC’s costs to $10,000.

Reports to risk management

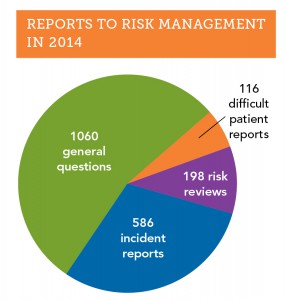

The risk management hotline is one of the most utilized and valued services that OMIC provides to its insureds.  In 2014, 1,960 insureds and their staff called the hotline (see graph). Over half of the calls had to do with general risk management issues, such as documentation and record keeping, informed consent, HIPAA privacy, and proper advertising. Calls about “difficult patients” were less frequent (116 reports) but were often challenging and time consuming because many aspects of care needed to be discussed, including the patient’s clinical and mental status, comorbidities, and payment issues. OMIC risk management staff work with the insured to craft an approach that resolves difficult patient situations so they do not escalate into claims.

In 2014, 1,960 insureds and their staff called the hotline (see graph). Over half of the calls had to do with general risk management issues, such as documentation and record keeping, informed consent, HIPAA privacy, and proper advertising. Calls about “difficult patients” were less frequent (116 reports) but were often challenging and time consuming because many aspects of care needed to be discussed, including the patient’s clinical and mental status, comorbidities, and payment issues. OMIC risk management staff work with the insured to craft an approach that resolves difficult patient situations so they do not escalate into claims.

Like the claims department, the OMIC risk management department also receives incident reports about adverse outcomes that may eventually become claims. In 2014, the risk management department received over 580 incident reports, approximately one-third of all calls to the hotline. Reports of incidents to the OMIC claims and risk management departments differ in important respects. First, all matters reported to the OMIC risk management department are kept strictly confidential; they are not shared with the underwriting or claims departments without the insured’s explicit permission. As a result, coverage is not triggered when an incident is first discussed with the risk management department, but insureds are encouraged to contact the claims department if the incident seems likely to result in a claim. At times, the best approach to managing an incident is to have risk management and claims work collaboratively with the insured, as the following case study demonstrates.

Last year, an insured called the risk management department to report a cluster of endophthalmitis cases in his retina practice. He believed the cluster arose from contaminated Avastin he had purchased from a compounding pharmacy in his state. On a Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday, the insured had injected 46 patients with the same lot of 70 syringes repackaged by the compounding pharmacy three weeks earlier. By Thursday of that week, four patients injected on Monday returned to his office with endophthalmitis. All four were immediately taken to surgery, tapped, and injected with antibiotics.

The insured contacted the compounding pharmacy that same day and reported his strong suspicion that the Avastin was contaminated. He also spoke to OMIC’s risk management department and was advised to sequester the remaining vials of Avastin and to contact the state health department, the Centers for Disease Control, and the Food and Drug Administration.

Not knowing how many other patients might have been affected or the exact cause of the endophthalmitis, the insured contacted all patients treated for age-related macular degeneration that week, including those who received Lucentis or Eyelea instead of Avastin. The insured had to cancel all his regularly scheduled patients over the next few days and worked over the weekend and into the middle of the following week in order to examine all the patients he had injected. As a precautionary measure, he prophylactically administered Vancomycin to all patients who had had intravitreal Avastin injections. Fortunately, no other patients developed endophthalmitis.

With the permission of the insured, OMIC’s claims department got involved and assigned a defense attorney. The defense attorney learned that an ophthalmologist from another state had reported a case of endophthalmitis from Avastin, bringing the total number of cases to five. The Avastin had come from the same compounding pharmacy and had been repackaged on the same day as the lot of syringes used by the OMIC insured. The pathology results from all five cases showed the same variant of streptococci.

To ensure that other ophthalmologists were notified, the insured and OMIC staff contacted the American Academy of Ophthalmology and the American Society of Retina Surgeons. The FDA, which had already been informed, issued a MedWatch Alert announcing a “voluntary recall” by the compounding pharmacy. In the recall, the FDA stated that syringes had been distributed to ophthalmic practices in Georgia, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Indiana. MedWatch advised ophthalmologists to immediately stop using lots of the recalled Avastin and to report any reactions or quality problems.

The story was picked up by the media. ABC online news compared these cases to the fungal infections following injection of contaminated medications from New England Compounding Center and similar prior endophthalmitis clusters that led to blindness after injection of compounded Avastin. ABC quoted the owner of the compounding pharmacy as stating: “We don’t know if the problem is with the vial from Genentech, our in-house procedures, or the physician’s office.”

The OMIC insured was contacted by a New York Times reporter for an interview. OMIC staff and defense counsel advised him not to talk with the media as this might compromise patient privacy and hamper the investigations being conducted by the FDA and state health department. The health department inspected the insured’s office the week following the outbreak and reviewed medical records for all patients who had received intravitreal injections during the at-risk period. The review was aimed at identifying risk factors for infection and evaluating office infection prevention practices. Inspectors found no deficiencies in injection technique or medication storage and handling at the insured’s office; however, they did identify multiple deficiencies at the compounding pharmacy in its repackaging process and determined that it had not complied with United States Pharmacopeial Chapter 797 (USP 797) standards for compounding or with recommended best practices for compounding Avastin.

With the assistance of retina specialists at a local university, the insured continued to care for the patients affected by endophthalmitis. The patients made no mention to the insured of filing a claim or lawsuit. Nonetheless, within a few weeks of the incident, the insured received a request for medical records from a well known plaintiff attorney representing three of the four patients who had developed endophthalmitis. Several months later, the plaintiff attorney called the insured’s office and requested an interview. The insured immediately contacted OMIC and the defense attorney who had already been assisting him. The defense attorney advised the plaintiff attorney that he was representing the insured and that all further contact with the insured should be through his office. The plaintiff attorney assured the defense attorney that the only target of the claim was the compounding pharmacy. Despite these assurances, defense counsel was concerned that any information revealed during such an interview could later be used against the insured in a lawsuit. As a general rule, OMIC and defense attorneys advise against informal interviews with plaintiff attorneys. In this case, OMIC claims staff and the attorney decided to allow the interview as long as the defense attorney was present to monitor the line of questioning and terminate the interview if it appeared necessary. Moreover, counsel felt the insured had handled the cluster of endophthalmitis cases in an exemplary manner, exercising good judgment in his quick identification and treatment of patients and notification of regulatory agencies. The interview with the plaintiff attorney was uneventful.

By promptly calling OMIC after identifying the cluster of endophthalmitis cases, the insured was able to avail himself of assistance from both the risk management and claims departments. With their help, he handled the clinical crisis and notified governmental agencies and the ophthalmic community quickly and effectively. The attorney assigned by OMIC helped the insured deal with the compounding pharmacy’s representatives and the patients’ attorney. While most incidents reported to OMIC are not as complex as this matter, this situation highlights the ability of OMIC staff to quickly muster the resources to help manage a fast-breaking incident.

When is a physician–patient relationship established?

PAUL WEBER, JD, ARM, Vice President, OMIC Risk Management/Legal

Plaintiffs who sue for medical malpractice must show that there was a physician-patient relationship that created a legal duty. OMIC has addressed the issue of a duty being established when the physician has not personally seen the patient in the context of on-call coverage for the emergency department, coverage arrangements with colleagues, and new referrals from other physicians. Articles and recommendations related to these situations can be found at www.omic.com. This article reviews an ophthalmologist’s duty to a patient that may arise from appointments with prospective patients and curbside consults.

Q When is a legal duty established between physician and patient?

A Unfortunately, there are no statutes specifically outlining and providing guidance to physicians on the circumstances that create this duty towards the patient. Instead, the legal basis for the physician-patient relationship arises out of court decisions that create precedents and vary by state. While there is no majority consensus, in general, the duty is established when a physician affirmatively acts in a patient’s care by diagnosing or treating the patient, or agreeing to do so. This area of law has evolved over decades so that now a physician-patient relationship may be established even when the physician does not personally see the patient, refuses to see the patient, or is unavailable to see the patient. Once the relationship is entered into, the physician owes a duty to the patient either to continue care or to properly terminate the relationship.

Q Can an appointment establish the physician-patient relationship?

A The general rule is that an appointment by a prospective patient to see an ophthalmologist by itself is not sufficient to establish a physician-patient relationship since an appointment does not necessarily mean the ophthalmologist has affirmatively acted or agreed to diagnose or treat the patient. However, since there is no “majority rule” on these issues, if a prospective patient misses a scheduled appointment, OMIC advises documenting your efforts to contact the prospective patient. Ophthalmologists generally may decline a request for an appointment but should have a policy to inform the prospective patient of the decision not to examine, diagnose, or treat and provide information about other options for care, e.g., the local hospital emergency room, local medical society, etc. When an ophthalmologist has granted an appointment for a specific consultation or procedure within his or her area of expertise, a duty to the patient can arise even prior to actually seeing the patient. However, if upon meeting and examining the patient, it is determined that the anticipated care is not needed or is beyond the ophthalmologist’s area of expertise, the patient should be referred to someone who can provide treatment. Once treatment has begun, regardless of whether it is within the ophthalmologist’s area of expertise, a relationship has been created and withdrawing from care at an unreasonable time or without affording the patient the opportunity to find a qualified provider may make the ophthalmologist liable for a claim of patient abandonment. OMIC insureds are encouraged to call the risk management hotline when they have concerns about withdrawing from care.

Q Can an informal “curbside consult” establish a physician-patient relationship?

A In the recent past, an informal opinion about a patient provided as a professional courtesy to a colleague did not typically establish a physician-patient relationship. Generally, if the patient’s identity was not disclosed, the patient was unaware of the consultation, and the consulting ophthalmologist did not bill for the advice, most courts would not have found a physician-patient relationship. Now, however, courts are increasingly allowing medical malpractice suits to proceed against specialists consulted informally. For that reason, it is important to follow general rules to avoid unintentionally establishing a physician-patient relationship when providing a curbside consult:1

- When consulted by other physicians, (a) frame responses in very general terms; (b) suggest several possible answers, noting that all are dependent on the specific circumstances of a particular case; and (c) include disclaimer statements to emphasize that there is no formal consulting relationship.

- Beware of evaluating test results of any kind and rendering a specific diagnosis.

- Keep all such conversations/communications short. If contacted by a treating physician a second time, consider suggesting a formal consultation.

- Document any such consultations with the date of the inquiry, the inquiring physician’s name, the nature of the inquiry, and any advice given. Without a record of the advice given, the consultant will be defenseless should a claim arise regarding the consultation.

These rules are based on the article “A Doctor’s Legal Duty—Erosion of the Curbside Consult” by Kimberly D. Baker of the Federation of Defense Lawyers and Defense Counsel.

Monovision misunderstanding leads to health department complaint

RYAN BUCSI, OMIC Senior Litigation Analyst

Allegation

Wrong powered lens placed during cataract surgery OS.

Disposition

Complaint dismissed by state department of health.

A patient presented to an OMIC insured with complaints of poor vision related to cataracts. The patient refused to wear glasses or contact lenses and wanted to explore treatment options that would not require either. The insured discussed monovision with the patient, explaining that an operation would be required on both eyes and if successful, one eye would be used for distance vision and the other for near vision. It was explained that prior to the procedure, the patient would be required to wear a contact lens to determine if she was indeed a candidate for monovision and would be comfortable with the anticipated results. The insured determined that the patient was naturally nearsighted and that the contact lens would be placed in the right eye for distance vision. Following the contact lens trial, the patient reported that she had inserted the contacts on only three occasions, but that on these three occasions, her vision was “just fine” and therefore she believed that undergoing the monovision procedure was a “good solution.” The insured agreed that the patient was a good candidate for monovision, so cataract surgery for distance vision was performed on the right eye. Subsequently, cataract surgery was performed on the left eye for near vision. During the one month postoperative exam, the patient complained of blurred vision in the left eye when looking at items in the distance. The insured reminded the patient that her distance vision in the left eye was not supposed to be similar to her distance vision in the right eye as this was not the intended outcome of the monovision procedure. The insured did note a slight overcorrection in the left eye, for which he recommended a piggy back lens; however, the monovision procedure was successful. Following this examination, the patient did not return to the OMIC insured.

Analysis

Five months after his last contact with the patient, the insured received a letter from his state’s department of health alerting him that the patient had filed a complaint. The patient alleged that the wrong powered lens was placed in the left eye and that she had to undergo a subsequent procedure to correct this error.

The insured promptly contacted OMIC and the case was referred to local defense counsel, which drafted a response letter to the state department of health. In the letter, defense counsel contended that the appropriate lens was placed in the left eye since the patient had agreed to monovision. Defense counsel was able to use informed consent documents and the insured’s medical records to prove that the patient was well aware that her right eye would be corrected for distance vision and her left eye would be corrected for near vision. Furthermore, the letter stated that following the procedure there was a slight overcorrection in the left eye. The exact reason for this overcorrection was unknown to the insured; however, it was possible that the lens itself shifted during the healing process. Defense counsel pointed out that this is a well known complication of the monovision procedure and in no way reflected a deviation from the standard of care. In addition, defense counsel retained a local expert who signed an affidavit stating that the care provided by the OMIC insured was well within the accepted standard of care. The combination of defense counsel’s letter and the supportive expert opinion prompted the state department of health to dismiss the patient’s complaint.

Risk management principles

Complaints from state health departments or medical boards should be referred to the OMIC claims department. No matter how “informal” a request for a response to a patient’s complaint may seem, these matters are serious and require legal representation in order to assure that the proper process is followed. This increases the likelihood that the complaint will be dismissed and may help the insured avoid a related medical malpractice claim or lawsuit. This case also highlights the importance of the informed consent process when discussing a complex treatment plan with a patient. The insured in this case did such a good job documenting his informed consent discussion that it provided defense counsel with enough evidence to convince the medical board that the patient was well aware of the parameters of treatment as well as the risks.

Regulatory and cyber (e-MD) liability resources

Coverage for the 14 different regulatory and cyber electronic media (e-MD) exposures is included in OMIC’s standard professional liability policy at no additional premium, subject to a per policy period sublimit of $100,000 per claim and in the aggregate. The sublimit for disciplinary proceedings related to direct patient treatment is $25,000. For a list and description of all 14 additional benefits included in your OMIC policy, visit www.omic.com/policyholder/benefits/.

On the policyholder benefits page you will find information under the following categories:

- Billing Errors (“Fraud and Abuse”) Allegations

- HIPAA/HITECH Privacy Violations

- Other Regulatory Exposures (DEA, Stark Act, EMTALA investigations)

- Licensure Actions

- Disciplinary Proceedings

- Cyber Liability and Network Vulnerabilities (e-MD)

With the move to electronic medical records, HIPAA and HITECH exposures related to cyber and electronic media breaches have increased for ophthalmic practices. Practices are also subject to a wide variety of potential losses as a result of network vulnerabilities, including damage to, or loss of, data. To assist policyholders, OMIC now has a dedicated web page devoted to cyber liability exposures. Visit the risk management section of OMIC’s website for articles, tools, links, and loss prevention resources.

Exclusively for policyholders

OMIC launched a Cyber Liability Risk Management Portal in 2014. Go to www.omic.com/risk-management/ for links to state-specific regulations, sample templates and protocols, employee notices and guidebooks, compliance plans, and coverage information. You must register or log in to MyOMIC services online to access the portal. The process is easy and takes just a few minutes. For live assistance, please contact the policyholder risk management hotline at 800.562.6642 (press 4) or email a risk manager at riskmanagement@omic.com.